В 2020 году глава Google заявил, что компания уже 13 лет является углеродно-нейтральной. Тренд на углеродную нейтральность поддерживают другие компании. Действительно ли это поможет преодолеть климатический кризис?

Углеродная нейтральность — термин, который означает, что компания сократила до нуля выбросы углекислого газа и его аналогов в процессе своей производственной деятельности или компенсировала эти выбросы за счет углеродно-отрицательных проектов.

Ученые разделяют выбросы компаний на три сферы охвата. Первая сфера охвата (Scope 1) — это прямые выбросы предприятия при производстве. Ко второй сфере охвата (Scope 2) относится потребление энергии. Важно понимать, из каких источников компания получает энергию: угольные станции, АЭС, ГЭС и другое. Третья сфера охвата (Scope 3) включает всю цепочку жизненного цикла товара: закупка сырья, доставка, продажа, использование, утилизация и прочее, то есть напрямую не относящиеся к производителю выбросы.

Три основных способа добиться углеродной нейтральности:

- сокращение прямых выбросов и переход на возобновляемые источники энергии — гидрогенерация, солнечная энергия, энергия ветра (Scope 1 и 2);

- прямой захват CO2 из воздуха;

- компенсация через инвестирование в проекты, которые сокращают выбросы углекислого газа.

Сокращение прямых выбросов

Этот способ считается самым эффективным, так как компания устраняет непосредственно источник выбросов CO2. Хорош он тем, что с его помощью легко определить шаги по сокращению выбросов, поскольку они прямые, а не косвенные. Последние заложены в длинную цепочку жизненного цикла товара, поэтому довольно сложно рассчитать компенсируемый объем эмиссии углекислого газа и определить конечного виновника.

Проблема же состоит в том, что этот путь связан с экономическими ограничениями — сокращение прямых выбросов часто сопряжено с уменьшением объема производства, а значит, с падением доходов предприятия. Если не сокращать производство, финансовых вложений потребуют технологии, которые бы снижали объем выбросов парниковых газов. Зачастую компании просто не идут на это из-за экономической нецелесообразности.

Прямой захват CO2 из воздуха

Прямой захват CO2 — это по сути «высасывание» углекислого газа из атмосферы. Его можно закопать под землю на длительное хранение или использовать в химических процессах для производства топлива, пластика и других материалов.

Самый распространенный метод захвата — пропустить воздух над специальной жидкостью. CO2 прилипает к смеси, а остальной воздух — нет. Затем смесь рециркулируют, выделяя углекислый газ с использованием тепла.

Биоэнергетика с улавливанием углерода (BECCS) — технология, которую можно отнести к прямому захвату выбросов, но улавливание идет не из атмосферы, а при сжигании биомассы. К биомассе относятся растения и сельскохозяйственные культуры.

Плюс такой технологии в том, что она имеет отрицательные выбросы. Растения через фотосинтез поглощают CO2, а когда их сжигают, они отдают углерод обратно, при этом происходит моментальное улавливание, и углерод не попадает в атмосферу. Таким образом растения поглощают углекислый газ, но затем обратно в атмосферу его не выделяют — так происходят отрицательные выбросы, то есть фактическое уменьшение углекислого газа в общем объеме.

Компенсация через инвестирование в углеродно-отрицательные проекты

Проектов по компенсации углекислого газа очень много. Это может быть как поддержка естественных природных процессов, так и помощь другим компаниям и некоммерческому сектору в сокращении выбросов парниковых газов.

К поддержке природного поглощения относится один из самых популярных способов компенсации — лесовосстановление. Но есть и другие менее известные — например, восстановление среды, где содержится «голубой углерод».

«Голубой углерод» — это углерод, который хранится в прибрежных или морских экосистемах. Мангровые заросли, болота и заросли водорослей по сути являются защитой от изменения климата, так как поглощают CO2 из атмосферы. Этот процесс происходит даже быстрее чем у лесов. Сегодня уже есть примеры того, как компании вкладывают деньги в восстановление мангровых лесов в Юго-Восточной Азии.

Другой способ — повышение продуктивности океана. В большинстве своем это пока лишь теоретические исследования. Одна из идей состоит в том, чтобы добавить питательное железо в те части океана, где его не хватает. Это должно вызвать ускоренное цветение микроскопических растений (фитопланктона), которые через фотосинтез улавливают углекислый газ.

Почему компенсация выбросов не решит проблему климата

Научно-консультативный совет европейских академий наук (EASAC) в 2018 году выпустил доклад, в котором говорится, что все известные технологии предлагают лишь ограниченный потенциал для удаления углекислого газа из атмосферы, то есть одними лишь компенсациями и прямым улавливанием мы не сможем достичь тех целей, которые ставит Парижское соглашение по климату. В отчете также говорится, что некоторые методы добиться углеродной нейтральности и вовсе могут нанести еще больший вред окружающей среде.

Пока технология по удалению углекислого газа нигде не применяется массово, поэтому сложно подсчитать экологический эффект от нее. Сам же метод требует большого количества энергетических и водных ресурсов, что может в будущем просто нивелировать положительный эффект от удаления CO2 и вызвать обратный результат. Более того, масштабное строительство сооружений для улавливания парниковых газов может негативно сказаться на земных и водных экосистемах.

Ученые пришли к общему мнению, что самый эффективный способ борьбы с изменением климата — прямое сокращение выбросов. «Основное внимание должно быть уделено смягчению последствий, сокращению выбросов парниковых газов. Это будет нелегко, но, несомненно, будет проще, чем применять углеродно-отрицательные технологии в значительных масштабах», — говорит профессор наук о Земле Оксфордского университета Гидеон Хендерсон.

По мнению Михаила Юлкина, гендиректора Центра экологических инвестиций и компании «КарбонЛаб», бизнес не должен ограничиваться только своими прямыми выбросами. «Если компания заявляет, что она углеродно-нейтральная только с точки зрения своих прямых выбросов (Scope 1), то это немного походит на гринвошинг. Углеродный след включает в себя все выбросы компании, связанные так или иначе с ее деятельностью: сырье, производство, поставка, использование, захоронение и переработка, то есть весь жизненный цикл продукта», — отмечает эксперт.

У российского нефтегазового сектора возникают сложности с пониманием того, что необходимо учитывать не только прямые выбросы от своего производства, но и косвенные, то есть те, которые образуются при использовании нефтепродуктов. По мнению Юлкина, подобные трудности есть и у автомобильной индустрии в России. Они готовы отчитываться за прямые выбросы, но в то же время перекладывают ответственность за автомобильные выхлопы на потребителей.

Что не так с посадками деревьев?

Лесовосстановление или облесение (выращивание леса там, где его никогда не было) для компаний самый понятный и простой в реализации способ компенсации углеродного следа. Но у этого метода есть свои недостатки.

Во-первых, лес очень долго растет. Чтобы дерево начало поглощать углекислый газ, должно пройти 15-20 лет, прежде чем оно вырастет из саженца во взрослое дерево. Во-вторых, деревья не так быстро поглощают CO2, то есть выполнить цели Парижского соглашения таким способом не получится. Средний показатель (сильно зависит от породы дерева) — около 4 т CO2 на 1 га леса в год. Например, рейс из Москвы в Сочи производит эмиссию углекислого газа в 13 т.

Отсюда вытекает другая проблема — необходимы огромные территории под посадки. Глава нефтегазового концерна Shell Бен ван Берден заявил о том, что нужно вырастить тропический лес размером с Бразилию, чтобы удержать потепление в пределах предписанных соглашением 1,5 °C, а это почти 6% от всей площади суши мира.

Самый важный вопрос состоит в том, можно ли считать высадки деревьев устойчивым лесоуправлением? «Чтобы деятельность считалась лесовосстановлением или облесением, участки должны быть переведены в лесной фонд, за ними должен быть контроль и учет. Компания должна нести полную ответственность за то, что происходит на территории. Если ты просто посадил деревья на пикнике, то это никакого отношения к поглощению углерода из атмосферы не имеет, это просто развлечение», — поясняет Юлкин из «КарбонЛаб».

Часто многие деревья просто не приживаются или умирают до того, как достигают зрелого возраста. В этом случае никакой компенсации выбросов не произойдет. Также необходимо понимать, что будет с деревом после его гибели, когда оно начнет выделять CO2 обратно. Если компания (или ответственный подрядчик) не следит и не контролирует свои посадки, а полагается на волю случая, то это скорее гринвошинг, а не компенсация.

Юлкин предлагает сначала проанализировать собственные технологии и понять, насколько они эффективны в устранении прямой эмиссии парниковых газов. Потом свести до минимума свои косвенные выбросы (Scope 3), а компенсировать лишь остаток. Вкладываться лучше в те проекты, которые гарантировано убирают источник парниковых газов, например, возобновляемая энергетика. «Лес — это не универсальный способ компенсировать выбросы, наоборот, один из самых сложных, хоть кажется самым доступным, но там много подводных камней» — говорит эксперт.

Как компании достигают углеродной нейтральности?

Глава ИТ-гиганта Google Сундар Пичаи осенью 2020 года сделал заявление о том, что уже в 2007 году компании удалось стать углеродно-нейтральной. Кроме того, она уже компенсировала все выбросы, произведенные ей за свою историю. Google также стал крупнейшим в мире покупателем возобновляемой энергии. В планах корпорации — к 2030 году полностью обеспечивать себя энергией из возобновляемых источников.

Что делает Google, чтобы быть углеродно-нейтральной компанией? Как и многие другие компании, она занимается посадками деревьев и спонсирует проекты, которые уменьшают количество углерода в атмосфере, например, очистка выбросов от свиноферм и мусорных свалок.

Другой ИТ-гигант Microsoft взял на себя обязательства удалить весь углерод, который он произвел с момента своего основания, то есть, с 1975 года. К 2030 году Microsoft планирует стать не просто нейтральной компанией, а углеродно-отрицательной, то есть удалять CO2 из атмосферы больше, чем производит.

К подобным заявлениям об углеродной нейтральности присоединилась и компания Apple. Она объявила, что будет инвестировать в развитие солнечной энергетики для собственного потребления и для малообеспеченных семей на Филиппинах, в восстановление мангровых лесов, разработку безуглеродного процесса плавки алюминия и другое.

О планах стать углеродно-нейтральной говорит одна из самых «грязных» индустрий — индустрия моды. Группа брендов Kering, куда входят Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen и другие, заявила, что будет стремиться к углеродной нейтральности и к 2025 году сократит собственные выбросы парниковых газов в два раза. Дом Gucci уже объявил себя полностью углеродно-нейтральным брендом.

Углеродно-нейтральными стремятся стать не только компании, но и международные мероприятия. В стратегии ФИФА есть обязательный пункт о компенсации выбросов, которые непосредственно может контролировать футбольная федерация.

Впрочем, более 50% всей эмиссии парниковых газов от проведения мировых турниров приходится на международные перелеты болельщиков. Эти выбросы ФИФА компенсирует по остаточному принципу — на те деньги, которые заплатили пассажиры в виде добровольного экологического сбора. За ЧМ-2018, который прошел в России, ФИФА компенсировала более 243 тыс. т контролируемых выбросов и 16 тыс. т выбросов от перелетов.

На какие проекты пошли деньги? Хоть чемпионат проходил в России, но деньги распределяются по всему миру.

- Так, в Костромской области в рамках ЧМ-2018 был проинвестирован переход деревообрабатывающего завода с ископаемого топлива на биомассу в качестве источника энергии. Биомассой стали древесные отходы самого предприятия, то есть, фактически, на заводе была внедрена циклическая экономика. До этого отходы попросту размещались на ближайшей свалке, выделяя метан.

- Еще шесть проектов было проинвестировано за пределами России. В Индии на реке Рангит построили гидроэлектростанцию. В качестве компенсации выбросов парниковых газов ФИФА также направила деньги в проект по модернизации обработки отходов свинофермы в Чили. В Кении было налажено производство электрических кухонных плит, которыми стали пользоваться преимущественно в сельской местности, чтобы заменить традиционные «очаги из трех камней». На завод по обработке пальмового масла в Таиланде было закуплено новое очистное оборудование. В Бразилии были построены две ГЭС, а в Пакистане — запущен проект по снижению выбросов оксида азота.

Следующий чемпионат мира по футболу, который пройдет в Катаре в 2022 году, по планам ФИФА должен стать углеродно-нейтральным, впервые в истории. Однако тут есть масса проблем — федерация может отвечать лишь за свои выбросы, но не за те, которые производят болельщики.

В идеальном сценарии компания, которая взяла курс на углеродную нейтральность, должна работать в двух направлениях. Приоритетное — сокращение своих выбросов при производстве и транспортировке продукта, а также переход на возобновляемые источники энергии, другое направление — инвестирование в углеродно-отрицательные проекты, чтобы компенсировать те выбросы, которые по каким-либо причинам убрать невозможно.

Подпишитесь на наш «Зеленый» канал в Telegram. Публикуем свежие исследования, эко-новости и советы, которые помогут жить, не вредя природе.

Carbon neutrality is a state of net zero carbon dioxide emissions. This can be achieved by ending the use of coal, oil and gas to the extent that there is dramatically reduced emissions of carbon dioxide and removal carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.[1] The term is used in the context of carbon dioxide-releasing processes associated with transport, energy production, agriculture, and industry.

Although the term «carbon neutral» is used, a carbon footprint also includes other greenhouse gases, measured in terms of their carbon dioxide equivalence. The term climate-neutral reflects the broader inclusiveness of other greenhouse gases in climate change, even if CO2 is the most abundant.

The term net zero is increasingly used to describe a broader and more comprehensive commitment to decarbonization and climate action, moving beyond carbon neutrality by including more activities under the scope of indirect emissions, and often including a science-based target on emissions reduction, as opposed to relying solely on offsetting. Some climate scientists have stated that «the idea of net zero has licensed a recklessly cavalier ‘burn now, pay later’ approach which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar.»[2]

Method[edit]

Carbon-neutral status can be achieved in two ways,[3] although a combination of the two is most likely required:

Ending emissions[edit]

Ending carbon emissions can be done by moving towards energy sources and industry processes that produce no greenhouse gases, thereby transitioning to a zero-carbon economy.[4] Shifting towards the use of renewable energy such as wind, geothermal, and solar power,[5] zero-energy systems like passive daytime radiative cooling,[6] as well as nuclear power,[7] reduces greenhouse gas emissions.[8] Although both renewable and non-renewable energy production produce carbon emissions in some form, renewable sources produce negligible to almost zero carbon emissions.[9] Transitioning to a low-carbon economy would also mean making changes to current industrial and agricultural processes to reduce carbon emissions, for example, diet changes to livestock such as cattle can potentially reduce methane production by 40%.[10] Carbon projects and emissions trading are often used to reduce carbon emissions, and carbon dioxide can even sometimes be prevented from entering the atmosphere entirely (such as by carbon scrubbing).

One way to implement carbon-neutral products is by making these products cheaper and more cost effective than carbon positive fuels.[11] Various companies have pledged to become carbon neutral or negative by 2050, some of which include: Microsoft,[12] Delta Air Lines,[13] BP,[13] IKEA,[14] and BlackRock,[15] although these distant pledges are typically not matched by real action and are often greenwashing – for instance with BP spending more on fossil fuels in 2022 than renewables despite its net zero pledge.[16]

Carbon offsetting[edit]

Balancing remaining carbon dioxide emissions with carbon offsets is the process of reducing or avoiding greenhouse gas emissions or removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to make up for emissions elsewhere.[17] If the total greenhouse gases emitted is equal to the total amount avoided or removed, then the two effects cancel each other out and the net emissions are ‘neutral’.[18]

Process[edit]

Carbon neutrality is usually achieved by combining the following steps, although these may vary depending whether the strategy is being implemented by individuals, companies, organizations, cities, regions, or countries:

Commitment[edit]

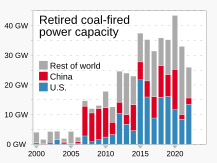

The annual amount of coal plant capacity being retired increased into the mid-2010s.[19] However, the rate of retirement has since stalled,[19] and global coal phase-out is not yet compatible with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement.[20]

In parallel with retirement of some coal plant capacity, other coal plants are still being added, though the annual amount of added capacity has been declining since the 2010s.[21]

In the case of individuals, decision-making is likely to be straightforward, but for more complex institutions it usually requires political leadership and popular agreement that the effort is worth making.

Commitment from countries and the organizations within is critical to the forward movement of Carbon Neutrality. The Net Zero Challenge Report states that «commitments made by governments so far are far from sufficient.»[22] One way to obtain more commitment would be to set carbon-neutral goals but allow flexibility for the organizations and governments to decide how to achieve these goals.[23]

Counting and analyzing[edit]

Counting and analyzing the emissions that need to be eliminated, and how it can be done, is an important step in the process of achieving carbon neutrality, as it establishes the priorities for where action needs to be taken and progress can begin being monitored. This can be achieved through a greenhouse gas inventory that aims to answer questions such as:

- Which operations, activities and units should be targeted?

- Which sources should be included (see section Direct and indirect emissions)?

- Who is responsible for which emissions?

- Which gases should be included?

For individuals, carbon calculators simplify compiling an inventory. Typically they measure electricity consumption in kWh, the amount and type of fuel used to heat water and warm the house, and how many kilometers an individual drives, flies and rides in different vehicles. Individuals may also set the limits of the system they are concerned with, for example, whether they want to balance out their personal greenhouse gas emissions, their household emissions, or their company’s.

There are plenty of carbon calculators available online, which vary significantly in the parameters they measure. Some, for example, factor in only cars, aircraft and household energy use. Others cover household waste or leisure interests as well. In some circumstances, going beyond carbon neutral and becoming carbon negative (usually after a certain length of time taken to reach carbon breakeven) is an objective.

Cities and countries are challenging for carbon counting and analyzing. This is because the production of goods and services within their territory can be linked either to domestic consumption or exports. On the other hand, citizens also consume imported goods and services. To avoid double counting in the calculation of emissions, it should be specified where the emissions should be counted: at the point of production or consumption. This can be complicated given the long production chains in a globalized economy.[24] In addition, embodied energy and the consequences of large-scale resource extraction needed for renewable energy systems and EV batteries are likely to present their own complications – local point-of-use emissions are likely to be greatly reduced, but life cycle emissions may still remain significant.[25]

Reduction[edit]

One of the strongest arguments for reducing greenhouse gas emissions is that it will often save money. Examples of possible actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are:

- Limiting energy usage and emissions from transportation (walking, using bicycles or public transport, avoiding flying, using low-energy vehicles, carpooling), as well as from buildings, equipment, animals and processes.

- Obtaining electricity and other forms of energy from zero or low carbon energy sources.

- Electrification: using electrical energy, ideally from non-emitting sources, rather than combustion. For example, in transportation (e.g., electric vehicles and electric trains) and heating (e.g. heat pumps and electric heating).[26]

Wind power, nuclear power, hydropower, solar power, and geothermal are the energy sources with the lowest life-cycle emissions, which includes deployment and operations.[5][8]

Offsetting[edit]

Carbon offsetting is the practice of removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere equivalent to the emissions generated by other activities. This is often done by paying «projects that either emit fewer emissions at source, such as cleaner energy production, or remove them from the atmosphere, such as forestry schemes.»[27] This aims to neutralize a certain volume of greenhouse gas emissions by funding activities which are expected to cause an equivalent reduction elsewhere, for example, with paid-for ecosystem services, such as blue carbon. Offsetting schemes can also have significant co-benefits such as improving quality of life and reducing poverty.[28]

Carbon offsetting has been critiqued on several fronts. One of the main concerns has been the potential for offsets to delay needed action on active emissions reductions.[29] In 2007, for example, in a report from the Transnational Institute, Kevin Smith likens carbon offsets to medieval indulgences where people pay «offset companies to absolve them of their carbon sins.»[30] This, he contends, permits a «business as usual» attitude that stifles the required major changes. Offsets have also been widely criticised for playing a part in greenwashing, an argument which has even mobilised in a 2021 watchdog ruling against Shell.[31]

Another critique of offsetting has been that loose regulation of claims by carbon offsetting schemes that, combined with the difficulties in calculating greenhouse gas sequestration and emissions reductions, can result in schemes that do not in reality adequately offset emissions.[29] Moves have been made to create better regulation. The United Nations, for instance, has operated a certification process for carbon offsets since 2001 called the Clean Development Mechanism.[32][33] This aims to stimulate «sustainable development and emission reductions, while giving industrialized countries some flexibility in how they meet their emission reduction limitation targets.»[32] However, the UK Government’s Climate Change Committee has also noted that «Although standards both globally and in the UK are being improved, the risk remains that the emissions reduction or removal reported may have happened anyway or may not persist into the future.»[29]

Criticisms have also been levelled at the use of non-native and monocultural forest plantations as carbon offsets for its «limited—and at times negative—effects on native biodiversity» and other ecosystem services.[34]

Evaluation and repeating[edit]

This phase includes evaluation of the results and compilation of a list of suggested improvements, with results documented and reported, so that experience gained of what does (and does not) work is shared with those who can put it to good use. Science and technology move on, regulations become tighter, the standards people demand go up. So the second cycle will go further than the first, and the process will continue, each successive phase building on and improving on what went before.[citation needed]

Being carbon neutral is increasingly seen as good corporate or state social responsibility and a growing list of corporations and states are announcing dates for when they intend to become fully neutral. Events such as the G8 Summit[35] and organizations like the World Bank[36] are also using offset schemes to become carbon neutral. Artists like The Rolling Stones[37] and Pink Floyd[38] have made albums or tours carbon neutral.

Direct and indirect emissions[edit]

To be considered carbon neutral, an organization must reduce its carbon footprint to zero. Determining what to include in the carbon footprint depends upon the organization and the standards they are following.

Generally, direct emissions sources must be reduced and offset completely, while indirect emissions from purchased electricity can be reduced with renewable energy purchases.[citation needed]

Direct emissions include all pollution from manufacturing, company owned vehicles and reimbursed travel, livestock and any other source that is directly controlled by the owner. Indirect emissions include all emissions that result from the use or purchase of a product. For instance, the direct emissions of an airline are all the jet fuel that is burned, while the indirect emissions include manufacture and disposal of airplanes, all the electricity used to operate the airline’s office, and the daily emissions from employee travel to and from work. In another example, the power company has a direct emission of greenhouse gas, while the office that purchases it considers it an indirect emission.[citation needed]

Cities and countries represent a challenge with regard to emissions counting as production of goods and services within their territory can be related either to domestic consumption or exports. Conversely the citizens also consume imported goods and services. To avoid double counting in any emissions calculation it should be made clear where the emissions are to be counted: at the site of production or consumption. This may be complicated given long production chains in a globalized economy. Moreover, the embodied energy and consequences of large-scale raw material extraction required for renewable energy systems and electric vehicle batteries is likely to represent its own complications – local emissions at the site of utilization are likely to be very small but life-cycle emissions can still be significant.[25]

Carbon is used as both a source of electricity and a feedstock in energy-intensive industries, making decarbonization impossible. If CO2 emissions and sources are to be captured and stopped from entering the atmosphere, an alternate chemical solution must be formulated that achieves the desired output while not releasing CO2 as a by-product.[39][40]

Simplification of standards and definitions[edit]

Carbon neutral fuels are those that neither contribute to nor reduce the amount of carbon into the atmosphere. Before an agency can certify an organization or individual as carbon neutral, it is important to specify whether indirect emissions are included in the Carbon Footprint calculation.[41] Most Voluntary Carbon neutral certifiers in the US, require both direct and indirect sources to be reduced and offset. As an example, for an organization to be certified carbon neutral, it must offset all direct and indirect emissions from travel by 1 lb CO2e per passenger mile, and all non-electricity direct emissions 100%.[42] Indirect electrical purchases must be equalized either with offsets, or renewable energy purchases. This standard differs slightly from the widely used World Resources Institute and may be easier to calculate and apply.[citation needed]

Much of the confusion in carbon neutral standards can be attributed to the number of voluntary carbon standards which are available. For organizations looking at which carbon offsets to purchase, knowing which standards are robust, credible and permanent is vital in choosing the right carbon offsets and projects to get involved in. Some of the main standards in the voluntary market include Verified Carbon Standard, Gold Standard and The American Carbon Registry. In addition companies can purchase Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) which result from mitigated carbon emissions from United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change approved projects for voluntary purposes. The concept of shared resources also reduces the volume of carbon a particular organization has to offset, with all upstream and downstream emissions the responsibility of other organizations or individuals. If all organizations and individuals were involved then this would not result in any double accounting.

Regarding terminology in UK, in December 2011 the Advertising Standards Authority (in an ASA decision which was upheld by its Independent Reviewer, Sir Hayden Phillips) controversially ruled that no manufactured product can be marketed as «zero-carbon», because carbon was inevitably emitted during its manufacture. This decision was made in relation to a solar panel system whose embodied carbon was repaid during 1.2 years of use and it appears to mean that no buildings or manufactured products can legitimately be described as zero carbon in its jurisdiction.[43]

Certification[edit]

Although there is currently no international certification scheme for carbon or climate neutrality, some countries have established national certification schemes. Examples include Norwegian Eco-Lighthouse Program and the Australian government’s Climate Active certification. In the private sector, organizations such as ClimatePartner can, for a fee, allow companies from many sectors to offset their carbon emissions using techniques like reforestation. These companies can then claim climate neutral status and even use the title online. However, there is no international clarity around these certifications and their validity.

Certifications are also available from the CEB,[44] BSI (PAS 2060) and The CarbonNeutral Company (CarbonNeutral).[45]

Criticism[edit]

Tracing the history of certain illusions in climate policy from 1988 to 2021, climate scientists James Dyke, Robert Watson, and Wolfgang Knorr «[arrive] at the painful realisation that the idea of net zero has licensed a recklessly cavalier ‘burn now, pay later’ approach which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar…

Current net zero policies will not keep warming to within 1.5 °C because they were never intended to. They were and still are driven by a need to protect business as usual, not the climate. If we want to keep people safe then large and sustained cuts to carbon emissions need to happen now. …The time for wishful thinking is over.»[2]

In March 2021, Tzeporah Berman, chair of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, argued that the Treaty would be a more genuine and realistic way to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement than the «Net zero» approach which, she claimed, is «delusional and based on bad science.»[46]

Eric Reguly, of The Globe and Mail states that, «The net-zero pledges are both welcome and dubious.

Most are back-end loaded, meaning the majority of the cuts are to come well after 2030… Most of these targets also assume…steady technological advances and outright breakthroughs…Fossil fuel exports will not figure into the national accounting for the net-zero goal.»[47]

In his 16-page report, Dangerous Distractions, economist Marc Lee states that, «‘Net zero’ has the potential to be a dangerous distraction that reduces the political pressure to achieve actual emission reductions…»[48][49] «A net zero target means less incentive to get to ‘real zero’ emissions from fossil fuels, an escape hatch that perpetuates business as usual and delays more meaningful climate action…Rather than gambling on carbon removal technologies of the future, Canada should plan for a managed wind down of fossil fuel production and invest public resources in bona fide solutions like renewables and a just transition from fossil fuels.»[49][48]

History[edit]

Plenary session of the COP21 adopting the Paris Agreement in 2015

In 2006, the New Oxford American Dictionary made the term carbon-neutral word of the year.[50]

In December 2020, five years after the Paris Agreement, the Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres warned that the commitments made by countries in Paris were not sufficient and were not respected. He has urged all other countries to declare climate emergencies until carbon neutrality is reached.[51]

In May 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published Net Zero by 2050, a comprehensive study to demonstrate what changes would need to be done in order for the world to reach net zero carbon emissions by the year 2050. It compared the current state of affairs with projections matching the changes the report suggested in order to demonstrate a possible path towards the carbon neutrality goal.[52]

Examples of pledges[edit]

Being carbon neutral is increasingly seen as good corporate or state social responsibility, and a growing list of corporations, cities and states are announcing dates for when they intend to become fully neutral. Many countries have also announced dates by which they want to be carbon neutral, with many of them targeting the year 2050. However, setting an earlier date (i.e. 2025,[53] 2030,[54] or 2045[55]) may be considered to send out a stronger signal internationally,[56][57] and is recommended by the Climate Crisis Advisory Group.[58] Also, delaying significant action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is increasingly being considered to not be a financially sound idea.[59][60]

Companies and organizations[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (May 2019) |

The original Climate Neutral Network was an Oregon-based non-profit organization founded by Sue Hall and incorporated in 1999 to persuade companies that being climate neutral was potentially cost saving as well as environmentally sustainable. It developed both the Climate Neutral Certification and Climate Cool brand name with key stakeholders such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency, The Nature Conservancy, the Rocky Mountain Institute, Conservation International, and the World Resources Institute and succeeded in enrolling the 2002 Winter Olympics to compensate for its associated greenhouse gas emissions.[61]

Few companies have actually attained Climate Neutral Certification, applying to a rigorous review process and establishing that they have achieved absolute net zero or better impact on the world’s climate. Another reason that companies have difficulty in attaining the Climate Neutral Certification is due the lack clear guidelines on what it means to make a carbon neutral development.[62] Shaklee Corporation became the first Climate Neutral certified company in April 2000. The company employs a variety of investments, and offset activities, including tree-planting, use of solar energy, methane capture in abandoned mines and its manufacturing processes.[63] Climate Neutral Business Network states that it certified Dave Matthews Band’s concert tour as Climate Neutral. The Christian Science Monitor criticized the use of NativeEnergy, a for-profit company that sells offset credits to businesses and celebrities like Dave Matthews.[64]

Salt Spring Coffee became carbon neutral by lowering emissions through reducing long-range trucking and using bio-diesel fuel in delivery trucks,[65] upgrading to energy efficient equipment and purchasing carbon offsets. The company claims to the first carbon neutral coffee sold in Canada.[66] Salt Spring Coffee was recognized by the David Suzuki Foundation in their 2010 report Doing Business in a New Climate.[67]

Some corporate examples of self-proclaimed carbon neutral and climate neutral initiatives include Dell,[68] Google,[69] HSBC,[70] ING Group,[71] PepsiCo, Sky Group,[72][73] Tesco,[74][75] Toronto-Dominion Bank,[76] Asos[77] and Bank of Montreal.[78]

Under the leadership of Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations pledged to work towards climate neutrality in December 2007. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) announced it was becoming climate neutral in 2008 and established a Climate Neutral Network to promote the idea in February 2008.

Events such as the G8 Summit and organizations like the World Bank are also using offset schemes to become carbon neutral. Artists like The Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd have made albums or tours carbon neutral, while Live Earth says that its seven concerts held on 7 July 2007 were the largest carbon neutral public event in history.

The Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games were the first carbon neutral Games in history.[79]

Buildings, in 2019, made up 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[80]: 7 The American Institute of Architects 2030 Commitment is a voluntary program for AIA member firms and other entities in the built environment that asks these organizations to pledge to design all their buildings to be carbon neutral by 2030.[81]

In 2010, architectural firm HOK worked with energy and daylighting consultant The Weidt Group to design a 170,735-square-foot (15,861.8 m2) net zero carbon emissions Class A office building prototype in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.[82]

Goodvalley[83] became a carbon neutral company as the first pork meat producer. It was possible by lowering greenhouse gases emission at every stage of production. In addition to reducing its primary carbon footprint, the company achieves carbon neutrality by producing green energy from its agricultural biogas plants. The sum of CO2 emissions and reductions are calculated by NIRAS and since 2018, the calculation has labelled Goodvalley Group Corporate Carbon Neutral. The certification is done according to ISO-14064 and verified by TÜV Rheinland.[84]

Since 2019, an increasing number of business organisations have committed to attaining carbon neutrality by, or before, 2050,[85] such as Microsoft (2030), Amazon (2040), and L’Oreal (2050).[86]

In 2020, BlackRock, the world’s largest investment firm, announced that it would begin making decisions with climate change and sustainability in mind, and begin exiting assets that it believed represented a «high sustainablilty-related risk».[87] Activists have accused the company of greenwashing, as it still has a considerable amount of money invested in coal companies.[88] In CEO Larry Fink’s 2021 annual letter, however, he further pushed for businesses to begin laying out explicit plans on how they will be carbon neutral by 2050.[89]

Countries and nations[edit]

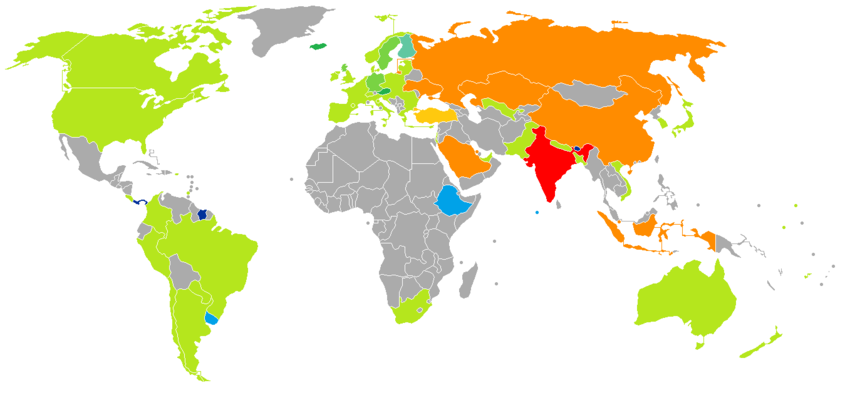

Countries and nations by intended year of climate neutrality

Carbon neutral or negative

2030

2035

2040

2045

2050

2053

2060

2070

Unknown or undeclared

Eight countries have achieved or surpassed carbon neutrality:Bhutan, Comoros, Gabon, Guyana, Madagascar, Niue, Panama, Suriname. Those countries generally protect their ecosystems and have relatively little industry sector. Gabon has been described as a model for environmental conservation while Suriname has begun to use its forests for carbon credits.[90]

The 3 carbon negative countries formed a small coalition at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference and asked for help so that other countries will join it.[94]

As of October 2021, numerous countries/nations have pledged carbon neutrality, including:[95][96]

| Country/nation | Target | Source(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Status | ||

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [97] | |

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [98] | |

| 2050 | Law | [99] | |

| 2040 | Coalition agreement | [96][100][101][102] | |

| 2060 | Statement of intent | [103] | |

| 2050 | Under discussion | [104] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [105] | |

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [106] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96] | |

| 2060 | Policy position | [107] | |

| 2050 | Under discussion | [96] | |

| 2050 | Statement of intent | [108][109] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2050 | Statement of intent | [110] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96] | |

| 2025 or 2030 | Policy position | [111][112] | |

| 2050 | Political agreement | [113][114] | |

| 2050 | Pledged towards the Paris agreement | [96] | |

| 2035 | Coalition agreement | [96] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96] | |

| 2040 | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2070 | Pledge | [115] | |

| 2060 | Policy position | [104] | |

| 2045 | Law | [116] | |

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [96] | |

| 2050 | Under discussion | [104] | |

| 2050 | Coalition agreement | [96] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [117] | |

| 2050 | Law | [118] | |

| 2060 | Submission to UNFCCC | [119] | |

| 2050 | Law | [120][104] | |

| 2030 | Submission to UNFCCC | [120] | |

| 2050 | Pledged towards the Paris agreement | [96] | |

| [121] | |||

| 2050 | Policy position | [104] | |

| 2050 | Pledged towards the Paris agreement | [96] | |

| 2050 | Pledge |

[122] |

|

| 2050 | Law | [123] | |

| 2050 | Under discussion | [104] | |

| 2050 (actual) | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2030 (offsets) | |||

| 2050 | Under discussion | [104] | |

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [96] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [124] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [125] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2060 | Pledge | [126] | |

| 2060 | Pledge | [127] | |

| 2045 | Law | [128] | |

| 2060 | Submission to UNFCCC | [96] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [129] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [96] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96][130] | |

| 2060 | Policy position | [104] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96][131] | |

| 2045 | Law | [96][132] | |

| 2050 | Policy position | [96] | |

| [133] | |||

| 2053 | Policy position | [134] | |

| 2060 | Statement of intent | [135][136] | |

| 2050 | Statement of intent | [137] | |

| 2050 | Statement of intent | [96] | |

| 2050 | Law | [96] | |

| 2030 | Pledged towards the Paris agreement | [96] | |

| 2050 | [138] | ||

| 2050 | Submission to UNFCCC | [98] | |

| 2050 | Pledge | [139] |

Canada[edit]

On 24 September 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged to make Canada carbon neutral by 2050 if re-elected.[140] On 21 October 2019, Trudeau was re-elected, and in December 2019, the Canadian government formally announced its goal for Canada to be carbon neutral by 2050.[141] In its speech from the throne, which was delivered on 23 September 2020, the federal government pledged to legislate its goal of making Canada carbon neutral by 2050.[142]

The city of Edmonton, Alberta, is currently developing a carbon neutral community called Blatchford, on the grounds of its former City Centre Airport.[143]

China[edit]

By 2020, China has announced its goal of achieving carbon neutrality and has decided to complete this strategic plan by 2060.[144] It suggested that economic growth does not necessarily have to slow down to attain the goal. Since the Communist Party’s 18th National Congress, China has completed 960 million mu (about 64 million hectares) afforestation. The forest cover increases by 2.68%–23.04%[145]

Costa Rica[edit]

Costa Rica aims to be fully carbon neutral by at least 2050.[146][147] In 2004, 46.7% of Costa Rica’s primary energy came from renewable sources,[148] while 94% of its electricity was generated from hydroelectric power, wind farms and geothermal energy in 2006.[149] A 3.5% tax on gasoline in the country is used for payments to compensate landowners for growing trees and protecting forests and its government is making further plans for reducing emissions from transport, farming and industry. In 2019, Costa Rica was one of the first countries that crafted a national decarbonization plan.[146]

European Union[edit]

The EU has intermediate targets and in 2019 the bloc, with the exception of Poland, agreed to set a 2050 target for carbon neutrality.[150]

The European Union has become the first area to embrace climate neutrality by 2050 through the European Green Deal, being committed to forming Green Alliances with partner nations and regions across the world.[151][152][153]

On 29 September 2021, the EU Commission launched 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030, one of the five EU missions. This EU mission aims to have 100+ carbon-neutral and smart cities by 2030 and also, inspire other cities towards the EU target of carbon neutrality by 2050.[154]

On 28 April 2022, the EU Commission announced a list of 112 cities, which were selected from more than 370 cities, who have pledged to be part of the EU mission’s goal of 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030.[155][154]

France[edit]

On 27 June 2019, the French National Assembly voted into law the first article in a climate and energy package that sets goals for France to cut its greenhouse gas emissions and go carbon-neutral by 2050 in line with the 2015 Paris climate agreement.[156] This was approved by the French Senate on 18 July 2019.[157]

Japan[edit]

In October 2020, Japan announced its plans to reach carbon neutrality in real terms by 2050, this passed the National Diet and was codified in law on 26 May 2021.[158]

Maldives[edit]

In March 2009, Mohamed Nasheed, then president of the Maldives, pledged to make his country carbon-neutral within a decade by moving to wind and solar power.[159] After he left the office, successive administrations abandoned the plan.[160]

New Zealand[edit]

On 7 November 2019, New Zealand passed a bill requiring the country to be net zero for all greenhouse gases by 2050 (with the exception of biogenic methane, with plans to reduce that by 24–47% below 2017 levels by 2050).[161][162][163]

Spain[edit]

In Spain, in 2014, the island of El Hierro became carbon neutral (for its power production).[164][165] Also, the city of Logroño Montecorvo in La Rioja will be carbon neutral once completed.[166][167]

In May 2021, Spain adopted the Climate Change and Energy Transition Law to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.[131] In October 2021, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez released Spain 2050 report which sets 50 milestones towards Spain’s goal to achieve carbon neutrality.[168]

Sweden[edit]

Sweden aims to become carbon neutral by 2045.[169] The Climate Act which enforces actions towards that goal was established in June 2017 and implemented in the beginning of 2018, making Sweden the first country with a legally-binding carbon neutrality target.[170] The vision is that net greenhouse gas emissions should be zero. The overall objective is that the increase in global temperature should be limited to two degrees, and that the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere stabilizes at a maximum of 400 ppm.[171]

In April 2022 an agreement between major parties in the Swedish Parliament was reached to include consumption and exports in its carbon neutrality target, which would make Sweden the first country in the world to include emissions from international trade in the pledges to mitigate climate change.[172]

South Korea[edit]

South Korea aims to be carbon neutral by 2050,[173][174] and enacted, on 31 August 2021, the enactment of the Carbon Neutral and Green Growth Basic Act, which stipulates the achievement of greenhouse gas reduction.[130] This bill, also called the ‘Climate Crisis Response Act’, mandates, by 2030, a 35% greenhouse gas reduction in the country compared to 2018.[130]

Vatican City[edit]

In July 2007, Vatican City announced a plan to become the first carbon-neutral state in the world, following the politics of the Pope to eliminate global warming. The goal would have been reached through a forest donated by a carbon offsetting company, which would have been located in the Bükk National Park, Hungary.[175] Eventually no trees were planted under the project and the carbon offsets did not materialise.[176][177]

In November 2008, the city state also installed and put into operation 2,400 solar panels on the roof of the Paul VI Centre audience hall.[178]

United Kingdom[edit]

As recommended by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) the government has legally committed to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the United Kingdom by 2050[179] and the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) has said it would be affordable. A range of techniques will be required including carbon sinks (greenhouse gas removal) in order to counterbalance emissions from agriculture and aviation. These carbon sinks might include reforestation, habitat restoration, soil carbon sequestration, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage and even direct air capture.[180]

In 2020, the UK government has linked attainment of net zero targets as a potential mechanism for improved air quality as a co-benefit.[181] The UK government estimated that eliminating fossil fuels for home heating and transportation could lead to a tripling of demand for electricity.[182]

Scotland[edit]

Scotland has set a 2045 target.[183] The islands of Orkney have significant wind and marine energy resources, and renewable energy has recently come into prominence. Although Orkney is connected to the mainland, it generates over 100% of its net power from renewables.[184][unreliable source?] This comes mainly from wind turbines situated right across Orkney

Thailand[edit]

Thailand aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.[185] As an initiative towards the carbon neutrality goal, Thailand’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment launched its first Carbon Credit Exchange in 2022.[187]

Taiwan[edit]

Taiwan has a 2050 target to achieve carbon neutrality.[188] The Department of Forestry and Nature Conservation, Chinese Culture University and Forestry Economics Division, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute presented a study in August 2012 indicating that afforestation can offset the carbon footprint to implementing carbon neutrality. They analyzed the carbon reduction benefits of afforested air quality enhancement zones (AQEZs) established by the government in 1995.[189]

United States[edit]

The United States has implemented carbon neutrality measures at both federal and state levels:

- the Presidency has set a goal of reducing carbon emissions by 50% to 52% compared to 2005 levels by 2030, a carbon free power sector by 2035, and to be net zero by 2050.[190]

- by April 2023, 23 states, plus Washington DC and Puerto Rico had set legislative or executive targets for clean power production.[191]

- all cars or light vehicles will have zero emissions (i.e. no internal combustion engine with gas or diesel) by 2035 in light duty vehicles, and no longer be bought by federal government by 2027.[192]

- the California Air Resources Board voted in 2022 to draft new rules banning gas furnaces and water heaters, and requiring zero emission appliances in 2030.[193] By 2022, four states have gas bans in new buildings.[194]

See also[edit]

- 2000-watt society

- Carbon emission trading

- Carbon fee and dividend

- Carbon footprint

- Carbon-neutral fuel

- Climate change mitigation

- Kardashev scale

- Live Earth

- Low-carbon diet

- Low Carbon Innovation Centre

- Nuclear power proposed as renewable energy

- Zero-energy building

Initiatives:

- Caring for Climate

- Carbon Neutrality Coalition

- Climate Clock

- Formula One — Net Zero Carbon by 2030;

References[edit]

- ^ «What is carbon neutrality and how can it be achieved by 2050? | News | European Parliament». www.europarl.europa.eu. 10 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ a b Dyke, James; Watson, Robert; Wolfgang, Knorr (22 April 2021). «Climate scientists: concept of net zero is a dangerous trap». The Conversation. The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ «What is carbon neutrality and how can it be achieved by 2050? | News | European Parliament». www.europarl.europa.eu. 10 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Hassanpouryouzband, Aliakbar; Joonaki, Edris; Edlmann, Katriona; Haszeldine, R. Stuart (2021). «Offshore Geological Storage of Hydrogen: Is This Our Best Option to Achieve Net-Zero?». ACS Energy Lett. 6 (6): 2181–2186. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00845. S2CID 236299486.

- ^ a b Adams, Samuel; Nsiah, Christian (November 2019). «Reducing carbon dioxide emissions; Does renewable energy matter?». Science of the Total Environment. 693: 133288. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.693m3288A. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.094. PMID 31357035. S2CID 198982966.

- ^ Liang, Jun; Wu, Jiawei; Guo, Jun; Li, Huagen; Zhou, Xianjun; Liang, Sheng; Qiu, Cheng-Wei; Tao, Guangming (September 2022). «Radiative cooling for passive thermal management towards sustainable carbon neutrality». National Science Review. 10 (1): nwac208. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwac208. PMC 9843130. PMID 36684522.

- ^ Nian, Victor; Mignacca, Benito; Locatelli, Giorgio (August 2022). «Policies toward net-zero: Benchmarking the economic competitiveness of nuclear against wind and solar energy». Applied Energy. 320: 119275. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119275. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 249223353.

- ^ a b «What is the role of nuclear power in the energy mix and in reducing greenhouse gas emissions?». Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment. 26 January 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ «Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy | EM SC 240N: Energy and Sustainability in Contemporary Culture». www.e-education.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Smith, Joshua (2019). «The race is on to cultivate a seaweed that slashes greenhouse emission from cows, other livestock». Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ «Last Energy raises $3 million to fight climate change with nuclear energy». VentureBeat. 25 February 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (16 January 2020). «Microsoft Pledges To Remove From The Atmosphere All The Carbon It Has Ever Emitted». NPR.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b «Delta And BP Pledge To Go Carbon-Neutral. How? That’s The Question». NPR.org. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Frangoul, Anmar (28 November 2019). «Ikea to invest $220 million to make it a ‘climate positive business’«. CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Wamsley, Laurel (14 January 2020). «World’s Largest Asset Manager Puts Climate At The Center Of Its Investment Strategy». NPR.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ A Lawson, ‘BP criticised over plan to spend billions more on fossil fuels than green energy’ (27 December 2022) Guardian

- ^ Carbon-Neutral Is Hip, but Is It Green? Archived 25 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, published 2007-04-29, accessed 3 August 2007

- ^ Levin, Kelly; Fransen, Taryn; Schumer, Clea; Davis, Chantal; Boehm, Sophie (17 September 2019). «What Does «Net-Zero Emissions» Mean? 8 Common Questions, Answered». Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b «Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker». Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. — Global Energy Monitor’s Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Shared attribution: Global Energy Monitor, CREA, E3G, Reclaim Finance, Sierra Club, SFOC, Kiko Network, CAN Europe, Bangladesh Groups, ACJCE, Chile Sustentable (5 April 2023). «Boom and Bust Coal / Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline» (PDF). Global Energy Monitor. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker». Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. — Global Energy Monitor’s Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ «Which countries and companies have a net-zero carbon emissions target, and what’s their progress like?». World Economic Forum (weforum.org).

- ^ «Carbon Neutrality: 7 Strategies for Success». Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (c2es.org).

- ^ Yamano, N. and Guilhoto, J.: CO2 emissions embodied in international trade and domestic final demand. OECD, Paris, 23 November 2020.

- ^ a b Huovila, Aapo; Siikavirta, Hanne; Antuña Rozado, Carmen; Rökman, Jyri; Tuominen, Pekka; Paiho, Satu; Hedman, Åsa; Ylén, Peter (2022). «Carbon-neutral cities: Critical review of theory and practice». Journal of Cleaner Production. 341: 130912. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130912. S2CID 246818806.

- ^ «How electrification can supercharge the energy transition». World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Forster, Piers. «Climate change: carbon offsetting isn’t working – here’s how to fix it». The Conversation. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ «CDM: CDM Development Benefits». cdm.unfccc.int. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Climate Change Committee (2022). Voluntary Carbon Markets and Offsetting (PDF) (Government Report). UK Government. p. 38.

- ^ Smith, Kevin (2007). The carbon neutral myth : offset indulgences for your climate sins. Oscar Reyes, Timothy Byakola, Carbon Trade Watch. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute. ISBN 978-90-71007-18-7. OCLC 778008109.

- ^ «Dutch Ad Watchdog Tells Shell to Pull ‘Carbon Neutral’ Campaign». Bloomberg.com. 27 August 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b «CDM: About CDM». cdm.unfccc.int. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ «United Nations online platform for voluntary cancellation of certified emission reductions (CERs)». offset.climateneutralnow.org. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Hua, Fangyuan; Bruijnzeel, L. Adrian; Meli, Paula; Martin, Philip A.; Zhang, Jun; Nakagawa, Shinichi; Miao, Xinran; Wang, Weiyi; McEvoy, Christopher; Peña-Arancibia, Jorge Luis; Brancalion, Pedro H. S.; Smith, Pete; Edwards, David P.; Balmford, Andrew (20 May 2022). «The biodiversity and ecosystem service contributions and trade-offs of forest restoration approaches». Science. 376 (6595): 839–844. Bibcode:2022Sci…376..839H. doi:10.1126/science.abl4649. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35298279. S2CID 247521598.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (7 June 2005). «The G8 summit promises to be a «carbon-neutral» event». BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ GreenBiz Admin (4 June 2006). «GreenBiz News |World Bank Group Goes Carbon-Neutral». Greenbiz.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ ClimateBiz Staff (4 September 2003). «GreenBiz News |Rolling Stones Pledge Carbon-Neutral U.K. Tour». Greenbiz.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Pink Floyd breathe life into new forests». prnewswire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «How it works: Innovation to decarbonise energy-intensive industries». European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Bandilla, Karl W. (2020). «Carbon Capture and Storage». Future Energy. pp. 669–692. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102886-5.00031-1. ISBN 9780081028865. S2CID 213619956.

- ^ «Carbon footprints will decrease in the Future». standardcarbon.com. Standard Carbon. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Carbon Neutral Travel». Archived from the original on 15 October 2007.

- ^ ««Zero Carbon Homes» in national ASA ban. UK Builders, Estate Agents, MP’s, Architects: take note». Solartwin.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «VER registry». www.en.ver.kbb.sk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ «Environmental Standards: Carbon Neutral». carbonneutral.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ Berman, Tzeporah; Nathan, Taft (3 March 2021). «Global oil companies have committed to ‘net zero’ emissions. It’s a sham». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Reguly, Eric (29 October 2021). «The net-zero pledges are dubious. Burning fossil fuels for economic growth remains the priority». The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ a b Lee, Marc (17 June 2021). «Dangerous Distractions: Canada’s carbon emissions and the pathway to net zero». Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ a b Lee, Marc (17 June 2021). «Net zero emissions: muddying the waters or real solutions?». Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ «Carbon Neutral: Oxford Word of the Year». Blog.oup.com. 13 November 2006. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Fiona Harvey (12 December 2020). «UN secretary general urges all countries to declare climate emergencies». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ IEA (2021), Net Zero by 2050, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050, License: CC BY 4.0

- ^ «Can we reach zero carbon by 2025?». Centre for Alternative Technology. 25 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ «Extinction Rebellion: What do they want and is it realistic?». BBC News. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ «Reducing greenhouse gases: our position | Policy and insight». policy.friendsoftheearth.uk. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ «Net Zero — The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming». Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Jones, Aled. «Net zero emissions by 2050 or 2025? Depends how you think politics works». The Conversation. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ «Head of Independent Sage to launch international climate change group». The Guardian. 20 June 2021. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Dyke, James. «Inaction on climate change risks leaving future generations $530 trillion in debt». The Conversation. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Hansen, James; Sato, Makiko; Kharecha, Pushker; von Schuckmann, Karina; Beerling, David J.; Cao, Junji; Marcott, Shaun; Masson-Delmotte, Valerie; Prather, Michael J.; Rohling, Eelco J.; Shakun, Jeremy; Smith, Pete; Lacis, Andrew; Russell, Gary; Ruedy, Reto (18 July 2017). «Young people’s burden: requirement of negative CO2 emissions». Earth System Dynamics. 8 (3): 577–616. arXiv:1609.05878. Bibcode:2017ESD…..8..577H. doi:10.5194/esd-8-577-2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021 – via esd.copernicus.org.

- ^ Ellison, Katherine (8 July 2002). «Burn Oil, Then Help A School Out; It All Evens Out». Money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Zuo, Jian; Read, Ben; Pullen, Stephen; Shi, Qian (1 April 2012). «Achieving carbon neutrality in commercial building developments – Perceptions of the construction industry». Habitat International. 36 (2): 278–286. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.10.010. ISSN 0197-3975. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ «SShaklee Heats Up Environmental Commitment By Going Climate Cool». Greenbiz.com. 17 May 2002. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ «Is Dave Matthews’ carbon offsets provider really carbon neutral?». CSMonitor.com. 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ Smith, Charlie (9 September 2004). «Biodiesel Revolution Gathering Momentum». The Georgia Straight. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ «Green goes mainstream». The Vancouver Sun. 15 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ «Doing Business in a New Climate: A Guide to Measuring, Reducing and Offsetting Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Publications | David Suzuki Foundation». Davidsuzuki.org. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ «Dell to go ‘carbon neutral’ by late 2008». Washingtonpost.com. 26 September 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Waters, Darren (19 June 2007). «Technology |Google’s drive for clean future». BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Business |HSBC bank to go carbon neutral». BBC News. 6 December 2004. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Climate Change and ING». Ceoroundtable.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Case Studies: Sky CarbonNeutral». Carbonneutral.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Horovitz, Bruce (30 April 2007). «PepsiCo takes top spot in global warming battle». Usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Business |Tesco boss unveils green pledges». BBC News. 18 January 2007. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Tesco wants to be carbon neutral by 2050. How will the retailer do it?». silicon.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «TD Greenhouse Gas Emissiona». Td.com. 7 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «News and media from The CarbonNeutral Company and clients — Natural Capital Partners». carbonneutral.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ «BMO Meets Carbon Neutral Commitment». Environmentalleader.com. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «Offsetting the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games». Offsetters.ca. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Cabeza, L. F., Q. Bai, P. Bertoldi, J.M. Kihila, A.F.P. Lucena, É. Mata, S. Mirasgedis, A. Novikova, Y. Saheb, 2022: Chapter 9: Buildings. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.011

- ^ «AIA Introduces 2030 Commitment Program to Reach Goal of Carbon Neutrality by 2030». Dexigner.com. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ «A Net Zero Office Today». 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010.

- ^ «Home».

- ^ «ID No. 0000039131: Goodvalley A/S — Certipedia». www.certipedia.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Green, Matthew (22 September 2019). «Big companies commit to slash emissions ahead of U.N. climate summit». Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Nguyen, Terry (5 March 2020). «More companies want to be «carbon neutral.» What does that mean?». Vox. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross (14 January 2020). «BlackRock C.E.O. Larry Fink: Climate Crisis Will Reshape Finance». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «BlackRock accused of ‘greenwashing’ $85bn coal investments». uk.finance.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Hansen, Sarah. «BlackRock’s Larry Fink Wants Companies To Eliminate Greenhouse Gas Emissions By 2050». Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f «These 8 countries have already achieved net-zero emissions». World Economic Forum. Energy Monitor. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Youn, Soo (17 October 2017). «Visit the World’s Only Carbon-Negative Country». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Walker, Robert (11 December 2018). «Heard Of This Small But Hugely Carbon Negative Country? Suriname In Amazonian Rain Forest». Science 2.0. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ «Suriname’s climate promise, for a sustainable future». UN News. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ a b Goering, Laurie (3 November 2021). «Forget net-zero: meet the small-nation, carbon-negative club». Reuters. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ «Members of the Carbon Neutrality Coalition». Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Darby, Megan (14 June 2019). «Which countries have a net zero carbon goal?». Climate Home News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ «NDC Update: Rwanda is First LDC in 2020, Andorra Commits to Carbon Neutrality by 2050 | News | SDG Knowledge Hub | IISD». SDG Knowledge Hub | Daily SDG News | IISD. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ a b Lombrana, Laura Millan; Shankleman, Jess; Ross, Tim (12 December 2020). «Xi Disappoints and Activists Slam Baby Steps: Climate Update». Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ «Climate Change Bill 2022». Parliament of Australia. 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ Huggler, Justin (2 January 2020). «New coalition to crack down on headscarves and make Austria carbon neutral by 2040». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. «Austria’s new government sets goal to be carbon neutral by 2040 | DW | 2 January 2020». DW.COM. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Freimuller, Martin (11 February 2020). «Austria’s new government sets goal to be carbon neutral by 2040». Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ «Bahrain aims to reach net zero carbon emissions in 2060 — BNA». Reuters. 24 October 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Net Zero Tracker». Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ «2050». Klimaat | Climat. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ França, Carlos Alberto Franco. «Brazil First NDC (Updated submission-letter)» (PDF). NDC Registry (interim). Brazilian Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ «China Pledges Carbon Neutrality by 2060 and Tighter Climate Goal». news.bloomberglaw.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ «Colombia». Carbon Neutrality Coalition. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «Colombia». climateactiontracker.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Spasić, Vladimir (29 January 2021). «Croatia aims to be climate neutral by 2050». Balkan Green Energy News. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ «Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)» (PDF). Environment, Forest and Climate Change Commission. Government of Ethiopia. p. 142. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Woldegebriel, E.G. (24 March 2015). «Can Ethiopia reach carbon neutrality by 2025?». World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «2050 long-term strategy». Climate Action — European Commission. 23 November 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «Committing to climate-neutrality by 2050: Commission proposes European Climate Law and consults on the European Climate Pact». European Commission. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (November 2021). «Narendra Modi pledges India will reach net zero emissions by 2070». The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ «German Cabinet approves landmark climate bill». DW.COM. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Surkes, Sue (29 October 2021). «Israel joins growing number of countries pledging to be carbon neutral by 2050». Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ «Editorial: Japan’s legal commitment to carbon-neutral 2050 must be catalyst for change». Mainichi Daily News. 1 June 2021. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Satubaldina, Assel (15 December 2020). «Tokayev Announces Kazakhstan’s Pledge to Reach Carbon Neutrality by 2060». The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b «Luxembourg». Carbon Neutrality Coalition. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «Mexico». Carbon Neutrality Coalition. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «Voortgang klimaatdoelen». rijksoverheid.nl. 24 September 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Wamsley, Laurel (7 November 2019). «New Zealand Commits To Being Carbon Neutral By 2050 — With A Big Loophole». npr. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ «Sustainable Development in Paraguay». Center for Sustainable Development — Columbia University. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ «Pledges And Targets | Climate Action Tracker». climateactiontracker.org. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ AFP (13 October 2021). «Russia Aiming for Carbon Neutrality by 2060, Putin Says». The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ «Saudi Arabia commits to net zero emissions by 2060». BBC News. 23 October 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ «Climate change — gov.scot». The Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Novak, Marja (14 January 2020). Cawthorne, Andrew (ed.). «Slovenia latest nation to seek carbon neutrality by 2050». Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b c «탄소중립기본법 통과». 연합뉴스 (in Korean). 31 August 2021. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ a b «Spain at last adopts promised law on becoming carbon neutral». AP NEWS. 13 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ «Sweden Plans to Be Carbon Neutral by 2045». UNFCCC. 19 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ «Timor-Leste». Carbon Neutrality Coalition. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ «Turkey to follow up climate deal ratification with action: Official». www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Marusyak, Bohdan (13 December 2020). «President Volodymyr Zelensky Announces Ukraine’s Climate Ambitions». Promote Ukraine. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ «Stuck in the middle: Ukraine aims for net zero but struggles to access finance». Climate Home News. 25 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ «UAE, a major carbon emitter, aims to go net-zero by 2050». www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Kawase, Kenji (31 January 2021). «Uzbekistan joins global carbon neutrality race to 2050». Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Vu, Minh (2 November 2021). «Vietnam pledges net zero emissions by 2050 at COP26». Hanoi Times. Hanoi Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Connolly, Amanada (24 September 2019). «Liberals pledge Canada will have net-zero emissions by 2050 — but details are scarce». Global News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.