| Galápagos tortoise

Temporal range: Holocene — Recent[1] |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Testudinidae |

| Genus: | Chelonoidis |

| Species: |

C. niger |

| Binomial name | |

| Chelonoidis niger

(Quoy & Gaimard, 1824) |

|

| Subspecies[2] | |

|

12 extant subspecies, 2 extinct subspecies |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

See section |

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger) is a species of very large tortoise in the genus Chelonoidis (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). The species comprises 15 subspecies (13 extant and 2 extinct). It is the largest living species of tortoise, with some modern Galápagos tortoises weighing up to 417 kg (919 lb).[3] They are also the largest extant terrestrial ectotherms. [4]

With lifespans in the wild of over 100 years, it is one of the longest-lived vertebrates. Captive Galapagos tortoises can live up to 177 years.[5] For example, a captive individual, Harriet, lived for at least 175 years. Spanish explorers, who discovered the islands in the 16th century, named them after the Spanish galápago, meaning «tortoise».[6]

Galápagos tortoises are native to seven of the Galápagos Islands. Shell size and shape vary between subspecies and populations. On islands with humid highlands, the tortoises are larger, with domed shells and short necks; on islands with dry lowlands, the tortoises are smaller, with «saddleback» shells and long necks. Charles Darwin’s observations of these differences on the second voyage of the Beagle in 1835, contributed to the development of his theory of evolution.

Tortoise numbers declined from over 250,000 in the 16th century to a low of around 15,000 in the 1970s. This decline was caused by overexploitation of the subspecies for meat and oil, habitat clearance for agriculture, and introduction of non-native animals to the islands, such as rats, goats, and pigs. The extinction of most giant tortoise lineages is thought to have also been caused by predation by humans or human ancestors, as the tortoises themselves have no natural predators. Tortoise populations on at least three islands have become extinct in historical times due to human activities. Specimens of these extinct taxa exist in several museums and also are being subjected to DNA analysis. 12 subspecies of the original 14-15 survive in the wild; a 13th subspecies (C. n. abingdonii) had only a single known living individual, kept in captivity and nicknamed Lonesome George until his death in June 2012. Two other subspecies, C. n. niger (the type subspecies of Galápagos tortoise) from Floreana Island and an undescribed subspecies from Santa Fe Island are known to have gone extinct in the mid-late 19th century. Conservation efforts, beginning in the 20th century, have resulted in thousands of captive-bred juveniles being released onto their ancestral home islands, and the total number of the subspecies is estimated to have exceeded 19,000 at the start of the 21st century. Despite this rebound, all surviving subspecies are classified as Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Galápagos tortoises are one of two insular radiations of giant tortoises that still survive to the modern day; the other is Aldabrachelys gigantea of Aldabra and the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, 700 km (430 mi) east of Tanzania. While giant tortoise radiations were common in prehistoric times, humans have wiped out the majority of them worldwide; the only other radiation of tortoises to survive to historic times, Cylindraspis of the Mascarenes, was driven to extinction by the 19th century, and other giant tortoise radiations such as a Centrochelys radiation on the Canary Islands and another Chelonoidis radiation in the Caribbean were driven to extinction prior to that.

Taxonomy[edit]

Early classification[edit]

The Galápagos Islands were discovered in 1535, but first appeared on the maps, of Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, around 1570.[7] The islands were named «Insulae de los Galopegos» (Islands of the Tortoises) in reference to the giant tortoises found there.[8][9][nb 1]

Initially, the giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean and those from the Galápagos were thought to be the same subspecies. Naturalists thought that sailors had transported the tortoises there.[10] In 1676, the pre-Linnaean authority Claude Perrault referred to both subspecies as Tortue des Indes.[11] In 1783, Johann Gottlob Schneider classified all giant tortoises as Testudo indica («Indian tortoise»).[12] In 1812, August Friedrich Schweigger named them Testudo gigantea («gigantic tortoise»).[13] In 1834, André Marie Constant Duméril and Gabriel Bibron classified the Galápagos tortoises as a separate subspecies, which they named Testudo nigrita («black tortoise»).[14]

Walter Rothschild, cataloger of two Galápagos tortoise subspecies

Recognition of subpopulations[edit]

The first systematic survey of giant tortoises was by the zoologist Albert Günther of the British Museum, in 1875.[15] Günther identified at least five distinct populations from the Galápagos, and three from the Indian Ocean islands. He expanded the list in 1877 to six from the Galápagos, four from the Seychelles, and four from the Mascarenes. Günther hypothesized that all the giant tortoises descended from a single ancestral population which spread by sunken land bridges.[16] This hypothesis was later disproven by the understanding that the Galápagos, the atolls of Seychelles, and the Mascarene islands are all of recent volcanic origin and have never been linked to a continent by land bridges. Galápagos tortoises are now thought to have descended from a South American ancestor,[17] while the Indian Ocean tortoises derived from ancestral populations on Madagascar.[18][19]

At the end of the 19th century, Georg Baur[20] and Walter Rothschild[21][22][23] recognised five more populations of Galápagos tortoise. In 1905–06, an expedition by the California Academy of Sciences, with Joseph R. Slevin in charge of reptiles, collected specimens which were studied by Academy herpetologist John Van Denburgh. He identified four additional populations,[24] and proposed the existence of 15 subspecies.[25] Van Denburgh’s list still guides the taxonomy of the Galápagos tortoise, though now 10 populations are thought to have existed.[26]

Current species and genus names[edit]

The current specific designation of niger, formerly feminized to nigra («black» – Quoy & Gaimard, 1824b[27]) was resurrected in 1984[28] after it was discovered to be the senior synonym (an older taxonomic synonym taking historical precedence) for the then commonly used subspecies name of elephantopus («elephant-footed» – Harlan, 1827[29]). Quoy and Gaimard’s Latin description explains the use of nigra: «Testudo toto corpore nigro» means «tortoise with completely black body». Quoy and Gairmard described nigra from a living specimen, but no evidence indicates they knew of its accurate provenance within the Galápagos – the locality was in fact given as California. Garman proposed the linking of nigra with the extinct Floreana subspecies.[30] Later, Pritchard deemed it convenient to accept this designation, despite its tenuousness, for minimal disruption to the already confused nomenclature of the subspecies. The even more senior subspecies synonym of californiana («californian» – Quoy & Gaimard, 1824a[31]) is considered a nomen oblitum («forgotten name»).[32]

Previously, the Galápagos tortoise was considered to belong to the genus Geochelone, known as ‘typical tortoises’ or ‘terrestrial turtles’. In the 1990s, subgenus Chelonoidis was elevated to generic status based on phylogenetic evidence which grouped the South American members of Geochelone into an independent clade (branch of the tree of life).[33] This nomenclature has been adopted by several authorities.[2][26][34][35]

Subspecies[edit]

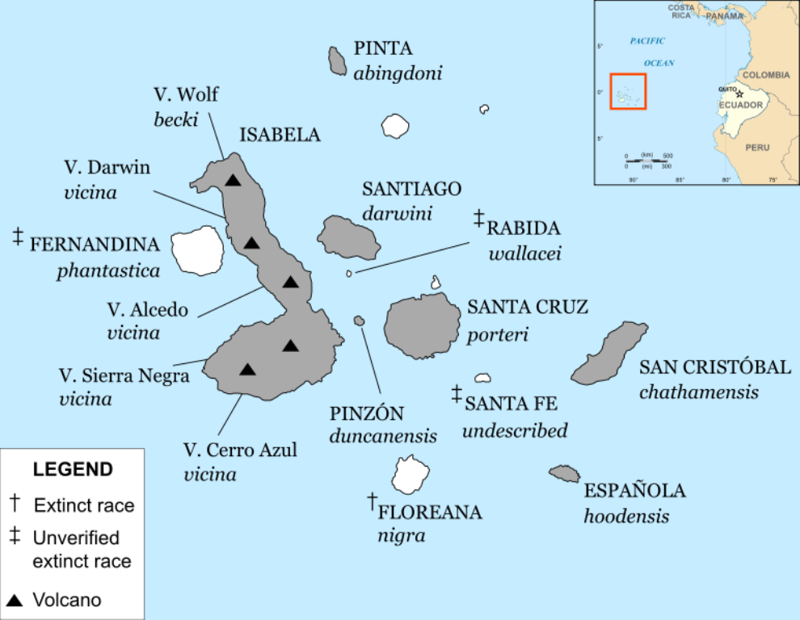

Galápagos archipelago annotated with ranges of currently recognised subspecies of Galápagos tortoise, islands with surviving subspecies are shaded. Note that several subspecies have been resurrected or described since the map was made, phantastica has been rediscovered, and wallacei is no longer considered valid.

Within the archipelago, 14-15 subspecies of Galápagos tortoises have been identified, although only 12 survive to this day. Five are found on separate islands; five of them on the volcanoes of Isabela Island. Several of the surviving subspecies are seriously endangered.[17] A 13th subspecies, C. n. abingdonii from Pinta Island, is extinct since 2012. The last known specimen, named Lonesome George, died in captivity on 24 June 2012; George had been mated with female tortoises of several other subspecies, but none of the eggs from these pairings hatched. The subspecies inhabiting Floreana Island (G. niger)[36] is thought to have been hunted to extinction by 1850,[37][38] only 15 years after Charles Darwin’s landmark visit of 1835, when he saw shells, but no live tortoises there.[39] However, recent DNA testing shows that an intermixed, non-native population currently existing on the island of Isabela is of genetic resemblance to the subspecies native to Floreana, suggesting that G. niger has not gone entirely extinct.[36] The existence of the C. n. phantastica subspecies of Fernandina Island was disputed, as it was described from a single specimen that may have been an artificial introduction to the island; however, a live female was found in 2019, likely confirming the subspecies’ validity.[40][41][42][43][44]

Prior to widespread knowledge of the differences between the populations (sometimes called races) from different islands and volcanoes, captive collections in zoos were indiscriminately mixed. Fertile offspring resulted from pairings of animals from different races. However, captive crosses between tortoises from different races have lower fertility and higher mortality than those between tortoises of the same race,[45][46] and captives in mixed herds normally direct courtship only toward members of the same race.[46]

The valid scientific names of each of the individual populations are not universally accepted,[47][41][48][49] and some researchers still consider each subspecies to be distinct species.[50][51] Prior to 2021, all subspecies were classified as distinct species from one another, but a 2021 study analyzing the level of divergence within the extinct West Indian Chelonoidis radiation and comparing it to the Galápagos radiation found that the level of divergence within both clades may have been significantly overestimated, and supported once again reclassifying all Galápagos tortoises as subspecies of a single subspecies, C. niger.[52] This was followed by the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group and the Reptile Database later that year.[53][54] The taxonomic status of the various races is not fully resolved.[55]

Evolutionary history[edit]

All subspecies of Galápagos tortoises evolved from common ancestors that arrived from mainland South America by overwater dispersal. Genetic studies have shown that the Chaco tortoise of Argentina and Paraguay is their closest living relative.[17] The minimal founding population was a pregnant female or a breeding pair.[17] Survival on the 1000-km oceanic journey is accounted for because the tortoises are buoyant, can breathe by extending their necks above the water, and are able to survive months without food or fresh water.[33] As they are poor swimmers, the journey was probably a passive one facilitated by the Humboldt Current, which diverts westwards towards the Galápagos Islands from the mainland.[63] The ancestors of the genus Chelonoidis are believed to have similarly dispersed from Africa to South America during the Oligocene.[33]

The closest living relative (though not a direct ancestor) of the Galápagos giant tortoise is the Chaco tortoise (Chelonoidis chilensis), a much smaller subspecies from South America. The divergence between C. chilensis and C. niger probably occurred 11.95–25 million years ago, an evolutionary event preceding the volcanic formation of the oldest modern Galápagos Islands 5 million years ago.[64][65][66] Mitochondrial DNA analysis indicates that the oldest existing islands (Española and San Cristóbal) were colonised first, and that these populations seeded the younger islands via dispersal in a «stepping stone» fashion via local currents.[67][68] Restricted gene flow between isolated islands then resulted in the independent evolution of the populations into the divergent forms observed in the modern subspecies. The evolutionary relationships between the subspecies thus echo the volcanic history of the islands.[17]

Subspecies[edit]

Modern DNA methods have revealed new information on the relationships between the subspecies:

Isabela Island

The five populations living on the largest island, Isabela, are the ones that are the subject of the most debate as to whether they are true subspecies or just distinct populations or subspecies. It is widely accepted that the population living on the northernmost volcano, Volcan Wolf, is genetically independent from the four populations to the south and is therefore a separate subspecies.[17] It is thought to be derived from a different colonization event than the others. A colonization from the island of Santiago apparently gave rise to the Volcan Wolf subspecies (C. n. becki) while the four southern populations are believed to be descended from a second colonization from the more southerly island of Santa Cruz.[17] Tortoises from Santa Cruz are thought to have first colonized the Sierra Negra volcano, which was the first of the island’s volcanoes to form. The tortoises then spread north to each newly created volcano, resulting in the populations living on Volcan Alcedo and then Volcan Darwin. Recent genetic evidence shows that these two populations are genetically distinct from each other and from the population living on Sierra Negra (C. guentheri) and therefore form the subspecies C. n. vandenburghi (Alcedo) and C. n. microphyes (Darwin).[69] The fifth population living on the southernmost volcano (C. n. vicina) is thought to have split off from the Sierra Negra population more recently and is therefore not as genetically different as the other two.[69] Isabela is the most recently formed island tortoises inhabit, so its populations have had less time to evolve independently than populations on other islands, but according to some researchers, they are all genetically different and should each be considered as separate subspecies.[69]

Floreana Island

Phylogenetic analysis may help to «resurrect» the extinct subspecies of Floreana (C. n. niger) – a subspecies known only from subfossil remains.[38] Some tortoises from Isabela were found to be a partial match for the genetic profile of Floreana specimens from museum collections, possibly indicating the presence of hybrids from a population transported by humans from Floreana to Isabela,[51] resulting either from individuals deliberately transported between the islands,[70] or from individuals thrown overboard from ships to lighten the load.[20] Nine Floreana descendants have been identified in the captive population of the Fausto Llerena Breeding Center on Santa Cruz; the genetic footprint was identified in the genomes of hybrid offspring. This allows the possibility of re-establishing a reconstructed subspecies from selective breeding of the hybrid animals.[71] Furthermore, individuals from the subspecies possibly are still extant. Genetic analysis from a sample of tortoises from Volcan Wolf found 84 first-generation C. n. niger hybrids, some less than 15 years old. The genetic diversity of these individuals is estimated to have required 38 C. n. niger parents, many of which could still be alive on Isabela Island.[72]

Pinta Island

The Pinta Island subspecies (C. n. abingdonii, now extinct) has been found to be most closely related to the subspecies on the islands of San Cristóbal (C. n. chathamensis) and Española (C. n. hoodensis) which lie over 300 km (190 mi) away,[17] rather than that on the neighbouring island of Isabela as previously assumed. This relationship is attributable to dispersal by the strong local current from San Cristóbal towards Pinta.[73] This discovery informed further attempts to preserve the C. n. abingdonii lineage and the search for an appropriate mate for Lonesome George, which had been penned with females from Isabela.[74] Hope was bolstered by the discovery of a C. n. abingdonii hybrid male in the Volcán Wolf population on northern Isabela, raising the possibility that more undiscovered living Pinta descendants exist.[75]

Santa Cruz Island

Mitochondrial DNA studies of tortoises on Santa Cruz show up to three genetically distinct lineages found in nonoverlapping population distributions around the regions of Cerro Montura, Cerro Fatal, and La Caseta.[76] Although traditionally grouped into a single subspecies (C. n. porteri), the lineages are all more closely related to tortoises on other islands than to each other:[77] Cerro Montura tortoises are most closely related to C. n. duncanensis from Pinzón,[63] Cerro Fatal to C. n. chathamensis from San Cristóbal,[63][78][79] and La Caseta to the four southern races of Isabela[63][79] as well as Floreana tortoises.[79]

In 2015, the Cerro Fatal tortoises were described as a distinct taxon, donfaustoi.[79][80] Prior to the identification of this subspecies through genetic analysis, it was noted that there existed differences in shells between the Cerro Fatal tortoises and other tortoises on Santa Cruz.[81] By classifying the Cerro Fatal tortoises into a new taxon, greater attention can be paid to protecting its habitat, according to Adalgisa Caccone, who is a member of the team making this classification.[79][81]

Pinzón Island

When it was discovered that the central, small island of Pinzón had only 100–200 very old adults and no young tortoises had survived into adulthood for perhaps more than 70 years, the resident scientists initiated what would eventually become the Giant Tortoise Breeding and Rearing Program. Over the next 50 years, this program resulted in major successes in the recovery of giant tortoise populations throughout the archipelago.

In 1965, the first tortoise eggs collected from natural nests on Pinzón Island were brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station, where they would complete the period of incubation and then hatch, becoming the first young tortoises to be reared in captivity. The introduction of black rats onto Pinzón sometime in the latter half of the 19th century had resulted in the complete eradication of all young tortoises. Black rats had been eating both tortoise eggs and hatchlings, effectively destroying the future of the tortoise population. Only the longevity of giant tortoises allowed them to survive until the Galápagos National Park, Island Conservation, Charles Darwin Foundation, the Raptor Center, and Bell Laboratories removed invasive rats in 2012. In 2013, heralding an important step in Pinzón tortoise recovery, hatchlings emerged from native Pinzón tortoise nests on the island and the Galápagos National Park successfully returned 118 hatchlings to their native island home. Partners returned to Pinzón Island in late 2014 and continued to observe hatchling tortoises (now older), indicating that natural recruitment is occurring on the island unimpeded. They also discovered a snail subspecies new to science. These exciting results highlight the conservation value of this important management action. In early 2015, after extensive monitoring, partners confirmed that Pinzón and Plaza Sur Islands are now both rodent-free.[82]

Española Island

On the southern island of Española, only 14 adult tortoises were found, two males and 12 females. The tortoises apparently were not encountering one another, so no reproduction was occurring. Between 1963 and 1974, all 14 adult tortoises discovered on the island were brought to the tortoise center on Santa Cruz and a tortoise breeding program was initiated. In 1977, a third Española male tortoise was returned to Galapagos from the San Diego Zoo and joined the breeding group.[83] After 40 years’ work reintroducing captive animals, a detailed study of the island’s ecosystem has confirmed it has a stable, breeding population. Where once 15 were known, now more than 1,000 giant tortoises inhabit the island of Española. One research team has found that more than half the tortoises released since the first reintroductions are still alive, and they are breeding well enough for the population to progress onward, unaided.[84] In January 2020, it was widely reported that Diego, a 100-year-old male tortoise, resurrected 40% of the tortoise population on the island and is known as the «Playboy Tortoise».[85]

Fernandina Island

The C. n. phantasticus subspecies from Fernandina was originally known from a single specimen — an old male from the voyage of 1905–06.[25] No other tortoises or remains were found on the island for a long time after its sighting, leading to suggestions that the specimen was an artificial introduction from elsewhere.[41][42][70] Fernandina has neither human settlements nor feral mammals, so if this subspecies ever did exist, its extinction would have been by natural means, such as volcanic activity.[41] Nevertheless, there have occasionally been reports from Fernandina.[86] In 2019, an elderly female specimen was finally discovered on Fernandina and transferred to a breeding center, and trace evidence found on the expedition indicates that more individuals likely exist in the wild. It has been theorized that the rarity of the subspecies may be due to the harsh habitat it survives in, such as the lava flows that are known to frequently cover the island.[43]

Santa Fe Island[edit]

The extinct Santa Fe subspecies has not yet been described and thus has no binomial name, having been identified from the limited evidence of bone fragments (but no shells, the most durable part) of 14 individuals, old eggs, and old dung found on the island in 1905–06.[25] The island has never been inhabited by man nor had any introduced predators, but reports have been made of whalers hauling tortoises off the island.[70][87] Later genetic studies of the bone fragments indicate that the Santa Fe subspecies was distinct, and was most closely related to C. n. hoodensis.[87] A population of C. n. hoodensis has since been reintroduced to and established on the island to fill in the ecological role of the Santa Fe tortoise.[88]

Subspecies of doubtful existence

The purported Rábida Island subspecies (C. n. wallacei) was described from a single specimen collected by the California Academy of Sciences in December 1905,[25] which has since been lost. This individual was probably an artificial introduction from another island that was originally penned on Rábida next to a good anchorage, as no contemporary whaling or sealing logs mention removing tortoises from this island.[42]

Description[edit]

The tortoises have a large bony shell of a dull brown or grey color. The plates of the shell are fused with the ribs in a rigid protective structure that is integral to the skeleton. Lichens can grow on the shells of these slow-moving animals.[89] Tortoises keep a characteristic scute (shell segment) pattern on their shells throughout life, though the annual growth bands are not useful for determining age because the outer layers are worn off with time. A tortoise can withdraw its head, neck, and fore limbs into its shell for protection. The legs are large and stumpy, with dry, scaly skin and hard scales. The front legs have five claws, the back legs four.[25]

Gigantism[edit]

The discoverer of the Galápagos Islands, Fray Tomás de Berlanga, Bishop of Panama, wrote in 1535 of «such big tortoises that each could carry a man on top of himself.»[90] Naturalist Charles Darwin remarked after his trip three centuries later in 1835, «These animals grow to an immense size … several so large that it required six or eight men to lift them from the ground».[91] The largest recorded individuals have reached weights of over 400 kg (880 lb)[3][92] and lengths of 1.87 meters (6.1 ft).[27][93] Size overlap is extensive with the Aldabra giant tortoise, however taken as a subspecies, the Galápagos tortoise seems to average slightly larger, with weights in excess of 185 kg (408 lb) being slightly more commonplace.[94] Weights in the larger bodied subspecies range from 272 to 317 kg (600 to 699 lb) in mature males and from 136 to 181 kg (300 to 399 lb) in adult females.[25] However, the size is variable across the islands and subspecies; those from Pinzón Island are relatively small with a maximum known weight of 76 kg (168 lb) and carapace length of approximately 61 cm (24 in) compared to 75 to 150 cm (30 to 59 in) range in tortoises from Santa Cruz Island.[95] The tortoises’ gigantism was probably a trait useful on continents that was fortuitously helpful for successful colonisation of these remote oceanic islands rather than an example of evolved insular gigantism. Large tortoises would have a greater chance of surviving the journey over water from the mainland as they can hold their heads a greater height above the water level and have a smaller surface area/volume ratio, which reduces osmotic water loss. Their significant water and fat reserves would allow the tortoises to survive long ocean crossings without food or fresh water, and to endure the drought-prone climate of the islands. A larger size allowed them to better tolerate extremes of temperature due to gigantothermy.[96] Fossil giant tortoises from mainland South America have been described that support this hypothesis of gigantism that pre-existed the colonization of islands.[97]

Shell shape[edit]

Saddleback (C. n. abingdonii)

Intermediate (C. n. chathamensis)

Domed (C. n. porteri)

Galápagos tortoises possess two main shell forms that correlate with the biogeographic history of the subspecies group. They exhibit a spectrum of carapace morphology ranging from «saddleback» (denoting upward arching of the front edge of the shell resembling a saddle) to «domed» (denoting a rounded convex surface resembling a dome). When a saddleback tortoise withdraws its head and forelimbs into its shell, a large unprotected gap remains over the neck, evidence of the lack of predation during the evolution of this structure. Larger islands with humid highlands over 800 m (2,600 ft) in elevation, such as Santa Cruz, have abundant vegetation near the ground.[49] Tortoises native to these environments tend to have domed shells and are larger, with shorter necks and limbs. Saddleback tortoises originate from small islands less than 500 m (1,600 ft) in elevation with dry habitats (e.g. Española and Pinzón) that are more limited in food and other resources.[63] Two lineages of Galápagos tortoises possess the Island of Santa Cruz and when observed it is concluded that despite the shared similarities of growth patterns and morphological changes observed during growth, the two lineages and two sexes can be distinguished on the basis of distinct carapace features. Lineages differ by the shape of the vertebral and pleural scutes. Females have a more elongated and wider carapace shape than males. Carapace shape changes with growth, with vertebral scutes becoming narrower and pleural scutes becoming larger during late ontogeny.

- Evolutionary implications

In combination with proportionally longer necks and limbs,[25] the unusual saddleback carapace structure is thought to be an adaptation to increase vertical reach, which enables the tortoise to browse tall vegetation such as the Opuntia (prickly pear) cactus that grows in arid environments.[98] Saddlebacks are more territorial[93][99] and smaller than domed varieties, possibly adaptations to limited resources. Alternatively, larger tortoises may be better-suited to high elevations because they can resist the cooler temperatures that occur with cloud cover or fog.[48]

A competing hypothesis is that, rather than being principally a feeding adaptation, the distinctive saddle shape and longer extremities might have been a secondary sexual characteristic of saddleback males. Male competition over mates is settled by dominance displays on the basis of vertical neck height rather than body size[48] (see below). This correlates with the observation that saddleback males are more aggressive than domed males.[100] The shell distortion and elongation of the limbs and neck in saddlebacks is probably an evolutionary compromise between the need for a small body size in dry conditions and a high vertical reach for dominance displays.[48]

The saddleback carapace probably evolved independently several times in dry habitats,[93] since genetic similarity between populations does not correspond to carapace shape.[101] Saddleback tortoises are, therefore, not necessarily more closely related to each other than to their domed counterparts, as shape is not determined by a similar genetic background, but by a similar ecological one.[48]

- Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is most pronounced in saddleback populations in which males have more angled and higher front openings, giving a more extreme saddled appearance.[100] Males of all varieties generally have longer tails and shorter, concave plastrons with thickened knobs at the back edge to facilitate mating. Males are larger than females — adult males weigh around 272–317 kg (600–699 lb) while females are 136–181 kg (300–399 lb).[48]

Behavior[edit]

A tortoise bathing in a pool

Routine[edit]

The tortoises are ectothermic (cold-blooded), so they bask for 1–2 hours after dawn to absorb the sun’s heat through their dark shells before actively foraging for 8–9 hours a day.[41] They travel mostly in the early morning or late afternoon between resting and grazing areas. They have been observed to walk at a speed of 0.3 km/h (0.2 mph).[91]

On the larger and more humid islands, the tortoises seasonally migrate between low elevations, which become grassy plains in the wet season, and meadowed areas of higher elevation (up to 2,000 ft (610 m)[25]) in the dry season. The same routes have been used for many generations, creating well-defined paths through the undergrowth known as «tortoise highways».[49] On these wetter islands, the domed tortoises are gregarious and often found in large herds, in contrast to the more solitary and territorial disposition of the saddleback tortoises.

Tortoises sometimes rest in mud wallows or rain-formed pools, which may be both a thermoregulatory response during cool nights, and a protection from parasites such as mosquitoes and ticks.[49] Parasites are countered by taking dust baths in loose soil. Some tortoises have been noted to shelter at night under overhanging rocks.[102] Others have been observed sleeping in a snug depression in the earth or brush called a «pallet». Local tortoises using the same pallet sites, such as on Volcán Alcedo, results in the formation of small, sandy pits.[103]

Diet[edit]

The tortoises are herbivores that consume a diet of cacti, grasses, leaves, lichens, berries, melons, oranges and milkweed.[104] They have been documented feeding on Hippomane mancinella (poison apple), the endemic guava Psidium galapageium, the water fern Azolla microphylla, bromeliad Tillandsia insularis and the Galápagos tomato Solanum cheesmaniae.[105] Juvenile tortoises eat an average of 16.7% of their own body weight in dry matter per day, with a digestive efficiency roughly equal to that of hindgut-fermenting herbivorous mammals such as horses and rhinos.[106]

Tortoises acquire most of their moisture from the dew and sap in vegetation (particularly the Opuntia cactus); therefore, they can survive longer than 6 months without water. They can endure up to a year when deprived of all food and water,[107] surviving by breaking down their body fat to produce water as a byproduct. Tortoises also have very slow metabolisms.[108] When thirsty, they may drink large quantities of water very quickly, storing it in their bladders and the «root of the neck» (the pericardium[41]), both of which served to make them useful water sources on ships.[107] On arid islands, tortoises lick morning dew from boulders, and the repeated action over many generations has formed half-sphere depressions in the rock.[41]

Senses[edit]

Regarding their senses, Charles Darwin observed, «The inhabitants believe that these animals are absolutely deaf; certainly they do not overhear a person walking near behind them. I was always amused, when overtaking one of these great monsters as it was quietly pacing along, to see how suddenly, the instant I passed, it would draw in its head and legs, and uttering a deep hiss fall to the ground with a heavy sound, as if struck dead.»[91] Although they are not deaf,[25] tortoises depend far more on vision and smell as stimuli than hearing.[49]

Mutualism[edit]

Tortoises share a mutualistic relationship with some subspecies of Galápagos finch and mockingbirds. The birds benefit from the food source and the tortoises get rid of irritating ectoparasites.[109]

Small groups of finches initiate the process by hopping on the ground in an exaggerated fashion facing the tortoise. The tortoise signals it is ready by rising up and extending its neck and legs, enabling the birds to reach otherwise inaccessible spots on the tortoise’s body such as the neck, rear legs, cloacal opening, and skin between plastron and carapace.

Some tortoises have been observed to exploit this mutualistic relationship to consume birds seeking to groom them. After rising and extending its limbs, the bird may go beneath the tortoise to investigate, whereupon suddenly the tortoise withdraws its limbs to drop flat and kill the bird. It then steps back to eat the bird, presumably to supplement its diet with protein.[110]

A pair of tortoises engaging in a dominance display

Mating[edit]

Mating occurs at any time of the year, although it does have seasonal peaks between February and June in the humid uplands during the rainy season.[49] When mature males meet in the mating season, they face each other in a ritualised dominance display, rise up on their legs, and stretch up their necks with their mouths gaping open. Occasionally, head-biting occurs, but usually the shorter tortoise backs off, conceding mating rights to the victor. The behaviour is most pronounced in saddleback subspecies, which are more aggressive and have longer necks.[100]

The prelude to mating can be very aggressive, as the male forcefully rams the female’s shell with his own and nips her legs.[61] Mounting is an awkward process and the male must stretch and tense to maintain equilibrium in a slanting position. The concave underside of the male’s shell helps him to balance when straddled over the female’s shell, and brings his cloacal vent (which houses the penis) closer to the female’s dilated cloaca. During mating, the male vocalises with hoarse bellows and grunts,[102] described as «rhythmic groans».[49] This is one of the few vocalisations the tortoise makes; other noises are made during aggressive encounters, when struggling to right themselves, and hissing as they withdraw into their shells due to the forceful expulsion of air.[111]

A young tortoise and a tortoise egg

Egg-laying[edit]

Females journey up to several kilometres in July to November to reach nesting areas of dry, sandy coast. Nest digging is a tiring and elaborate task which may take the female several hours a day over many days to complete.[49] It is carried out blindly using only the hind legs to dig a 30 cm (12 in)-deep cylindrical hole, in which the tortoise then lays up to 16 spherical, hard-shelled eggs ranging from 82 to 157 grams (2.9 to 5.5 oz) in mass,[41] and the size of a billiard ball.[89] Some observations suggest that the average clutch size for domed populations (9.6 per clutch for C. porteri on Santa Cruz) is larger than that of saddlebacks (4.6 per clutch for C. duncanensis on Pinzón).[42] The female makes a muddy plug for the nest hole out of soil mixed with urine, seals the nest by pressing down firmly with her plastron, and leaves them to be incubated by the sun. Females may lay one to four clutches per season. Temperature plays a role in the sex of the hatchlings, with lower-temperature nests producing more males and higher-temperature nests producing more females. This is related closely to incubation time, since clutches laid early incubate during the cool season and have longer incubation periods (producing more males), while eggs laid later incubate for a shorter period in the hot season (producing more females).[112]

Early life and maturation[edit]

Young animals emerge from the nest after four to eight months and may weigh only 50 g (1.8 oz) and measure 6 cm (2.4 in).[49] When the young tortoises emerge from their shells, they must dig their way to the surface, which can take several weeks, though their yolk sac can sustain them up to seven months.[89] In particularly dry conditions, the hatchlings may die underground if they are encased by hardened soil, while flooding of the nest area can drown them. Subspecies are initially indistinguishable as they all have domed carapaces. The young stay in warmer lowland areas for their first 10–15 years,[41] encountering hazards such as falling into cracks, being crushed by falling rocks, or excessive heat stress. The Galápagos hawk was formerly the sole native predator of the tortoise hatchlings; Darwin wrote: «The young tortoises, as soon as they are hatched, fall prey in great numbers to the buzzard».[91] The hawk is now much rarer, but introduced feral pigs, dogs, cats, and black rats have become predators of eggs and young tortoises.[113] The adult tortoises have no natural predators apart from humans; Darwin noted: «The old ones seem generally to die from accidents, as from falling down precipices. At least several of the inhabitants told me, they had never found one dead without some such apparent cause».[91]

Sexual maturity is reached at around 20–25 years in captivity, possibly 40 years in the wild.[114] Life expectancy in the wild is thought to be over 100 years,[115][116] making it one of the longest-lived subspecies in the animal kingdom. Harriet, a specimen kept in Australia Zoo, was the oldest known Galápagos tortoise, having reached an estimated age of more than 170 years before her death in 2006.[117] Chambers notes that Harriet was probably 169 years old in 2004, although media outlets claimed the greater age of 175 at death based on a less reliable timeline.[118]

Darwin’s development of theory of evolution[edit]

Charles Darwin as a young man, probably subsequent to the Galápagos visit

Charles Darwin visited the Galápagos for five weeks on the second voyage of HMS Beagle in 1835 and saw Galápagos tortoises on San Cristobal (Chatham) and Santiago (James) Islands.[119] They appeared several times in his writings and journals, and played a role in the development of the theory of evolution.

Darwin wrote in his account of the voyage:

I have not as yet noticed by far the most remarkable feature in the natural history of this archipelago; it is, that the different islands to a considerable extent are inhabited by a different set of beings. My attention was first called to this fact by the Vice-Governor, Mr. Lawson, declaring that the tortoises differed from the different islands, and that he could with certainty tell from which island any one was brought … The inhabitants, as I have said, state that they can distinguish the tortoises from the different islands; and that they differ not only in size, but in other characters. Captain Porter has described* those from Charles and from the nearest island to it, namely, Hood Island, as having their shells in front thick and turned up like a Spanish saddle, while the tortoises from James Island are rounder, blacker, and have a better taste when cooked.[120]

The significance of the differences in tortoises between islands did not strike him as important until it was too late, as he continued,

I did not for some time pay sufficient attention to this statement, and I had already partially mingled together the collections from two of the islands. I never dreamed that islands, about fifty or sixty miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted.[120]

Though the Beagle departed from the Galápagos with over 30 adult tortoises on deck, these were not for scientific study, but a source of fresh meat for the Pacific crossing. Their shells and bones were thrown overboard, leaving no remains with which to test any hypotheses.[121] It has been suggested[122] that this oversight was made because Darwin only reported seeing tortoises on San Cristóbal[123] (C. chathamensis) and Santiago[124] (C. darwini), both of which have an intermediate type of shell shape and are not particularly morphologically distinct from each other. Though he did visit Floreana, the C. niger subspecies found there was already nearly extinct and he was unlikely to have seen any mature animals.[39]

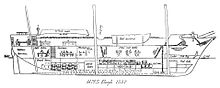

Line drawing of HMS Beagle by F. G. King, a colleague of Darwin’s: Galápagos tortoises were stacked in the lower hold.

However, Darwin did have four live juvenile specimens to compare from different islands. These were pet tortoises taken by himself (from San Salvador), his captain FitzRoy (two from Española) and his servant Syms Covington (from Floreana).[125] Unfortunately, they could not help to determine whether each island had its own variety because the specimens were not mature enough to exhibit morphological differences.[126] Although the British Museum had a few specimens, their provenance within the Galápagos was unknown.[127] However, conversations with the naturalist Gabriel Bibron, who had seen the mature tortoises of the Paris Natural History Museum confirmed to Darwin that distinct varieties occurred.[128]

Darwin later compared the different tortoise forms with those of mockingbirds, in the first[129] tentative statement linking his observations from the Galapagos with the possibility of subspecies transmuting:

When I recollect the fact that [from] the form of the body, shape of scales and general size, the Spaniards can at once pronounce from which island any tortoise may have been brought; when I see these islands in sight of each other and possessed of but a scanty stock of animals, tenanted by these birds, but slightly differing in structure and filling the same place in nature; I must suspect they are only varieties … If there is the slightest foundation for these remarks, the zoology of archipelagos will be well worth examining; for such facts would undermine the stability of subspecies.[130]

His views on the mutability of subspecies were restated in his notebooks: «animals on separate islands ought to become different if kept long enough apart with slightly differing circumstances. – Now Galapagos Tortoises, Mocking birds, Falkland Fox, Chiloe fox, – Inglish and Irish Hare.»[131] These observations served as counterexamples to the prevailing contemporary view that subspecies were individually created.

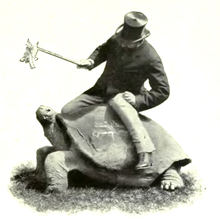

Darwin also found these «antediluvian animals»[123] to be a source of diversion: «I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away;—but I found it very difficult to keep my balance».[91]

Conservation[edit]

Several waves of human exploitation of the tortoises as a food source caused a decline in the total wild population from around 250,000[116] when first discovered in the 16th century to a low of 3,060 individuals in a 1974 census. Modern conservation efforts have subsequently brought tortoise numbers up to 19,317 (estimate for 1995–2009).[132]

The subspecies C. n. niger became extinct by human exploitation in the 19th century. Another subspecies, C. n. abingdonii, became extinct on 24 June 2012 with the death in captivity of the last remaining specimen, a male named Lonesome George, the world’s «rarest living creature».[133] All the other surviving subspecies are listed by the IUCN as at least «vulnerable» in conservation status, if not worse.[134]

C. n. porteri on Santa Cruz Island

Historical exploitation[edit]

An estimated 200,000 animals were taken before the 20th century.[41] The relatively immobile and defenceless tortoises were collected and stored live on board ships, where they could survive for at least a year without food or water (some anecdotal reports suggest individuals surviving two years[135]), providing valuable fresh meat, while their diluted urine and the water stored in their neck bags could be used as drinking water. The 17th-century English pirate, explorer, and naturalist William Dampier wrote, «They are so extraordinarily large and fat, and so sweet, that no pullet eats more pleasantly,»[136] while Captain James Colnett of the Royal Navy wrote of «the land tortoise which in whatever way it was dressed, was considered by all of us as the most delicious food we had ever tasted.»[137] US Navy captain David Porter declared, «after once tasting the Galapagos tortoises, every other animal food fell off greatly in our estimation … The meat of this animal is the easiest of digestion, and a quantity of it, exceeding that of any other food, can be eaten without experiencing the slightest of inconvenience.»[107] Darwin was less enthusiastic about the meat, writing «the breast-plate roasted (as the Gauchos do «carne con cuero»), with the flesh on it, is very good; and the young tortoises make excellent soup; but otherwise the meat to my taste is indifferent.»[138]

In the 17th century, pirates started to use the Galápagos Islands as a base for resupply, restocking on food and water, and repairing vessels before attacking Spanish colonies on the South American mainland. However, the Galápagos tortoises did not struggle for survival at this point because the islands were distant from busy shipping routes and harboured few valuable natural resources. As such, they remained unclaimed by any nation, uninhabited and uncharted. In comparison, the tortoises of the islands in the Indian Ocean were already facing extinction by the late 17th century.[139] Between the 1790s and the 1860s, whaling ships and fur sealers systematically collected tortoises in far greater numbers than the buccaneers preceding them.[140] Some were used for food and many more were killed for high-grade «turtle oil» from the late 19th century onward for lucrative sale to continental Ecuador.[141] A total of over 13,000 tortoises is recorded in the logs of whaling ships between 1831 and 1868, and an estimated 100,000 were taken before 1830.[135] Since it was easiest to collect tortoises around coastal zones, females were most vulnerable to depletion during the nesting season. The collection by whalers came to a halt eventually through a combination of the scarcity of tortoises that they had created and the competition from crude oil as a cheaper energy source.[142]

Galápagos tortoise exploitation dramatically increased with the onset of the California Gold Rush in 1849.[143] Tortoises and sea turtles were imported into San Francisco, Sacramento and various other Gold Rush towns throughout Alta California to feed the gold mining population. Galápagos tortoise and sea turtle bones were also recovered from the Gold Rush-era archaeological site, Thompson’s Cove (CA-SFR-186H), in San Francisco, California.[144]

Population decline accelerated with the early settlement of the islands in the early 19th century, leading to unregulated hunting for meat, habitat clearance for agriculture, and the introduction of alien mammal subspecies.[42] Feral pigs, dogs, cats, and black rats have become predators of eggs and young tortoises, whilst goats, donkeys, and cattle compete for grazing and trample nest sites. The extinction of the Floreana subspecies in the mid-19th century has been attributed to the combined pressures of hunting for the penal colony on the relatively small island, the conversion of the grazing highlands into land for farming and fruit plantations, and the introduction of feral mammals.[145]

Scientific collection expeditions took 661 tortoises between 1888 and 1930, and more than 120 tortoises have been taken by poachers since 1990. Threats continue today with the rapid expansion of the tourist industry and increasing size of human settlements on the islands.[146] The tortoises are down from 15 different types of subspecies when Darwin first arrived to the current 11 subspecies.[147]

Threats

- Introduced mammals

- Poachers

- Destruction of habitat

- Characteristics that make tortoises vulnerable

- Slow growth rate

- Late sexual maturity

- Can only be found on the Galápagos Islands

- Large size and slow-moving[147]

Collection

The tortoises of the Galápagos Islands were not only hunted for the oil that they held for fuel but also, once they were becoming more and more scarce, people began to pay to have them in their collections, as well as being put into museums.[148]

Modern conservation[edit]

Galápagos tortoise on Santa Cruz Island, Galápagos

The remaining subspecies of tortoise range in IUCN classification from extinct in the wild to vulnerable. Slow growth rate, late sexual maturity, and island endemism make the tortoises particularly prone to extinction without help from conservationists.[77] The Galápagos giant tortoise has become a flagship species for conservation efforts throughout the Galápagos.

Tourists see tortoises at the Charles Darwin Research Station

- Legal protection

The Galápagos giant tortoise is now strictly protected and is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered subspecies of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).[35] The listing requires that trade in the taxon and its products is subject to strict regulation by ratifying states, and international trade for primarily commercial purposes is prohibited. In 1936, the Ecuadorian government listed the giant tortoise as a protected subspecies. In 1959, it declared all uninhabited areas in the Galápagos to be a national park[149] and established the Charles Darwin Foundation. In 1970, capturing or removing many subspecies from the islands (including tortoises and their eggs) was banned.[150] To halt trade in the tortoises altogether, it became illegal to export the tortoises from Ecuador, captive or wild, continental, or insular in provenance. The banning of their exportation resulted in automatic prohibition of importation to the United States under Public Law 91-135 (1969).[151] A 1971 Ecuadorian decree made it illegal to damage, remove, alter, or disturb any organism, rock, or other natural object in the national park.[152]

Captive breeding[edit]

With the establishment of the Galapagos National Park and the CDF in 1959, a review of the status of the tortoise populations began. Only 11 of the 14 original populations remained and most of these were endangered if not already on the brink of extinction. The breeding and rearing program for giant tortoises began in response to the condition of the population on Pinzón, where fewer than 200 old adults were found. All of the hatchlings had been killed by introduced black rats, for perhaps more than a century. Without help, this population would eventually disappear. The only thing preserving it was the longevity of the tortoise.[153] Its genetic resistance to the negative effects of inbreeding would be another.[148]

Breeding and release programs began in 1965 and have successfully brought seven of the eight endangered subspecies up to less perilous population levels. Young tortoises are raised at several breeding centres across the islands to improve their survival during their vulnerable early development. Eggs are collected from threatened nesting sites, and the hatched young are given a head start by being kept in captivity for four to five years to reach a size with a much better chance of survival to adulthood, before release onto their native ranges.[113][132]

The most significant population recovery was that of the Española tortoise (C. n. hoodensis), which was saved from near-certain extinction. The population had been depleted to three males and 12 females that had been so widely dispersed that no mating in the wild had occurred.[154] Fruitless attempts to breed one of the tortoises, Lonesome George for example, is speculated to be attributed to a lack of postnatal cues,[155] and confusion over which would be the most appropriate genetic subspecies would be the most appropriate to mate him with on the islands.[17] The 15 remaining tortoises were brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station in 1971 for a captive breeding program[156] and, in the following 33 years, they gave rise to over 1,200 progeny which were released onto their home island and have since begun to reproduce naturally.[157][158] One of the tortoises, Diego, is one of the main drivers of a remarkable recovery of the hoodensis subspecies, having fathered between 350 and 800 progeny.[159]

Island restoration[edit]

The Galápagos National Park Service systematically culls feral predators and competitors. Goat eradication on islands, including Pinta, was achieved by the technique of using «Judas goats» with radio location collars to find the herds. Marksmen then shot all the goats except the Judas, and then returned weeks later to find the «Judas» and shoot the herd to which it had relocated. Goats were removed from Pinta Island after a 30-year eradication campaign, the largest removal of an insular goat population using ground-based methods. Over 41,000 goats were removed during the initial hunting effort (1971–82).[160] This process was repeated until only the «Judas» goat remained, which was then killed.[161] Other measures have included dog eradication from San Cristóbal, and fencing off nests to protect them from feral pigs.[113]

Efforts are now underway to repopulate islands formerly inhabited by tortoises to restore their ecosystems (island restoration) to their condition before humans arrived. The tortoises are a keystone species, acting as ecosystem engineers[161] which help in plant seed dispersal and trampling down brush and thinning the understory of vegetation (allowing light to penetrate and germination to occur). Birds such as flycatchers perch on and fly around tortoises to hunt the insects they displace from the brush.[89] In May 2010, 39 sterilised tortoises of hybrid origin were introduced to Pinta Island, the first tortoises there since the evacuation of Lonesome George 38 years before.[162] Sterile tortoises were released so the problem of interbreeding between subspecies would be avoided if any fertile tortoises were to be released in the future. It is hoped that with the recent identification of a hybrid C. n. abingdonii tortoise, the approximate genetic constitution of the original inhabitants of Pinta may eventually be restored with the identification and relocation of appropriate specimens to this island.[75] This approach may be used to «retortoise» Floreana in the future, since captive individuals have been found to be descended from the extinct original stock.[71]

Applied science[edit]

The Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Programme is a collaborative project coordinated by Dr Stephen Blake of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology. Its goal is to assist the Galapagos National Park to effectively conserve giant tortoises by conducting cutting-edge applied science, and developing an inspirational tortoise-based outreach and education programme. Since 2009, the project team have been analysing the movements of giant tortoises by tracking them via satellite tags. As of November 2014, the team have tagged 83 tortoises from four subspecies on three islands. They have established that giant tortoises conduct migrations up and down volcanoes, primarily in response to seasonal changes in the availability and quality of vegetation.[163] In 2015 they will start to track the movements of hatchling and juvenile tortoises, supported by the UK’s Galapagos Conservation Trust.[164]

See also[edit]

- List of subspecies of Galápagos tortoise

- Galápagos wildlife

Notes[edit]

- ^ The first navigation chart showing the individual islands was drawn up by the pirate Ambrose Cowley in 1684. He named them after fellow pirates or English noblemen. More recently, the Ecuadorian government gave most of the islands Spanish names. While the Spanish names are official, many researchers continue to use the older English names, particularly as those were the names used when Darwin visited. This article uses the Spanish island names.

References[edit]

- ^ «Fossilworks: Chelonoidis».

- ^ a b Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. (2016). Chelonoidis nigra. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T9023A97224409.en

- ^ a b White Matt (18 August 2015). «2002: Largest Tortoise». Official Guinness World Records. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02672.x.

- ^ Galapagos tortoise in the database AnAge

- ^ Woram, John (n.d.). «On the Origin of

Species‘Galápago’«. Las Encantadas: Human and Cartographic History of the Galápagos Islands. Rockville Press, Inc. Retrieved 21 September 2016. - ^ Stewart, P.D. (2006). Galápagos: the islands that changed the world. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-300-12230-5.

- ^ Pritchard 1996, p. 17

- ^ Jackson, Michael Hume (1993). Galápagos, a natural history. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-895176-07-0.

- ^ Chambers 2004, p. 27

- ^ Perrault, Claude (1676). Suite des memoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux (in French). Paris: Académie de Sciences. pp. 92–205.

- ^ Schneider, Johann Gottlob (1783). Allgemeine Naturgeschischte der Schildkröten nebs einem systematischen Verzeichnisse der einzelnen Arten und zwey Kupfen (in German). Leipzig. pp. 355–356. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Schweigger, August Friedrich (1812). «Prodromi monographiae chelonorum sectio prima». Archivfur Naturwissenschaft und Mathematik (in Latin). 1: 271–368, 406–462.

- ^ a b c Duméril, André Marie Constant; Bibron, Gabriel (1834). Erpétologie générale; ou, histoire naturelle complète des reptiles (in French). France: Librarie Encyclopédique de Roret.

- ^ a b c d e Günther, Albert (1875). «Description of the living and extinct races of gigantic land-tortoises. parts I. and II. introduction, and the tortoises of the Galapagos Islands». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 165: 251–284. Bibcode:1875RSPT..165..251G. doi:10.1098/rstl.1875.0007. JSTOR 109147.

- ^ Günther 1877, p. 9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Caccone, A.; Gibbs, J. P.; Ketmaier, V.; Suatoni, E.; Powell, J. R. (1999). «Origin and evolutionary relationships of giant Galapagos tortoises». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (23): 13223–13228. Bibcode:1999PNAS…9613223C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.23.13223. JSTOR 49147. PMC 23929. PMID 10557302.

- ^ Austin, Jeremy; Arnold, E. Nicholas (2001). «Ancient mitochondrial DNA and morphology elucidate an extinct island radiation of Indian Ocean giant tortoises (Cylindraspis)». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 268 (1485): 2515–2523. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1825. PMC 1088909. PMID 11749704.

- ^ Austin, Jeremy; Arnold, E. Nicholas; Bour, Roger (2003). «Was there a second adaptive radiation of giant tortoises in the Indian Ocean? Using mitochondrial DNA to investigate speciation and biogeography of Aldabrachelys«. Molecular Ecology. 12 (6): 1415–1424. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01842.x. PMID 12755871. S2CID 1518514.

- ^ a b c d Baur, G. (1889). «The Gigantic Land Tortoises of the Galapagos Islands» (PDF). The American Naturalist. 23 (276): 1039–1057. doi:10.1086/275045. S2CID 85198605. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b Rothschild, Walter (1901). «On a new land-tortoise from the Galapagos Islands». Novitates Zoologicae. 8: 372. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b Rothschild, Walter (1903). «Description of a new species of gigantic land tortoise from Indefatigable Island». Novitates Zoologicae. 10: 119. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Rothschild, Walter (1902). «Description of a new species of gigantic land tortoise from the Galápagos Islands». Novitates Zoologicae. 9: 619. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Van Denburgh, John (1907). «Preliminary descriptions of four new races of gigantic land tortoises from the Galapagos Islands». Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Series 4. 1: 1–6. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Van Denburgh, John (1914). «The gigantic land tortoises of the Galapagos archipelago». Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Series 4. 2 (1): 203–374.

- ^ a b c Rhodin, A.G.J.; van Dijk, P.P. (2010). Iverson, J.B.; Shaffer, H.B (eds.). Turtles of the World, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status. Turtle Taxonomy Working Group. Chelonian Research Foundation. pp. 33–34. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010. ISBN 978-0-9653540-9-7.

- ^ a b c d Quoy, J.R.C.; Gaimard, J.P. (1824b). «Sous-genre tortue de terre – testudo. brongn. tortue noire – testudo nigra. N.». In de Freycinet, M.L. (ed.). Voyage autour du Monde … exécuté sur les corvettes de L. M. «L’Uranie» et «La Physicienne,» pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820 (in French). Paris. pp. 174–175.

- ^ Pritchard, Peter Charles Howard (1984). «Further thoughts on Lonesome George». Noticias de Galápagos. 39: 20–23.

- ^ a b Harlan, Richard (1827). «Description of a land tortoise, from the Galápagos Islands, commonly known as the «Elephant Tortoise»«. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 5: 284–292. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Garman, Samuel (1917). «The Galapagos tortoises». Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College. 30 (4): 261–296.

- ^ a b c Quoy, J.R.C.; Gaimard, J.P. (1824). «Description d’une nouvelle espèce de tortue et de trois espèces nouvelles de scinques». Bulletin des Sciences Naturelles et de Géologie (in French). 1: 90–91.

- ^ Pritchard, Peter Charles Howard (1997). «Galapagos tortoise nomenclature: a reply». Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2: 619.

- ^ a b c Le, Minh; Raxworthy, Christopher J.; McCord, William P.; Mertz, Lisa (2006). «A molecular phylogeny of tortoises (Testudines:Testudinidae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear genes» (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (2): 517–531. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.03.003. PMID 16678445. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Fritz, U.; Havaš, P. (2007). «Checklist of Chelonians of the World» (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 149–368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b «CITES Appendices I, II and III 2011». 22 December 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b Poulakakis, Nikos; Glaberman, Scott; Russello, Michael; Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Ciofi, Claudio; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2008). «Historical DNA analysis reveals living descendants of an extinct species of Galapagos tortoise». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (40): 15464–15469. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10515464P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805340105. PMC 2563078. PMID 18809928.

- ^ Broom, R. (1929). «On the extinct Galápagos tortoise that inhabited Charles Island». Zoologica. 9 (8): 313–320.

- ^ a b Steadman, David W. (1986). «Holocene vertebrate fossils from Isla Floreana, Galápagos». Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 413 (413): 1–103. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.413. S2CID 129836489.

- ^ a b Sulloway, F.J. (1984). Berry, R.J (ed.). «Evolution in the Galápagos Islands: Darwin and the Galápagos». Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 21 (1–2): 29–60. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb02052.x.

- ^ Pritchard 1996, p. 63

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Swingland, I.R. (1989). Geochelone elephantopus. Galapagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland I.R. and Klemens M.W. (eds.) The Conservation Biology of Tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), No. 5, pp. 24–28. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 2-88032-986-8.

- ^ a b c d e MacFarland; Craig G.; Villa, José; Toro, Basilio (1974). «The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). I. Status of the surviving populations». Biological Conservation. 6 (2): 118–133. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(74)90024-X.

- ^ a b «Tortoise Feared Extinct Found on Remote Galapagos Island». The New York Times. Associated Press. 20 February 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ «Galápagos tortoise found alive is from species thought extinct». 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ MacFarland, Craig G.; Villa, José; Toro, Basilio (1974b). «The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part II: Conservation methods». Biological Conservation. 6 (3): 198–212. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(74)90068-8.

- ^ a b Márquez, Cruz; Fritts, Thomas H.; Koster, Friedmann; Rea, Solanda; Cepeda, Fausto; Llerena & Fausto (1995). «Comportamiento de apareamiento al azar en tortugas gigantes. Juveniles en cautiverio el las Islas Galápagos» (PDF). Revista de Ecología Latinoamericana (in Spanish). 3: 13–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Pritchard 1996, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e f Fritts, Thomas H. (1984). «Evolutionary divergence of giant tortoises in Galapagos». Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 21 (1–2): 165–176. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb02059.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i De Vries, T.J. (1984). The giant tortoises: a natural history disturbed by man. Key Environments: Galapagos. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 145–156. ISBN 978-0-08-027996-1.

- ^ Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger (1989). Turtles of the World. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-87474-414-9.

- ^ a b Poulakakis, Nikos; Glaberman, Scott; Russello, Michael; Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Ciofi, Claudio; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2008). «Historical DNA analysis reveals living descendants of an extinct species of Galapagos tortoise». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (40): 15464–15469. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10515464P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805340105. PMC 2563078. PMID 18809928.

- ^ Kehlmaier, Christian; Albury, Nancy A.; Steadman, David W.; Graciá, Eva; Franz, Richard; Fritz, Uwe (9 February 2021). «Ancient mitogenomics elucidates diversity of extinct West Indian tortoises». Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3224. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3224K. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82299-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7873039. PMID 33564028.

- ^ «Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group». Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ «Chelonoidis niger». The Reptile Database. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Zug, George R. (1997). «Galapagos tortoise nomenclature: still unresolved». The Journal of Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2 (4): 618–619. hdl:10088/11695.

- ^ Gray, John Edward (1853). «Description of a new species of tortoise (Testudo planiceps), from the Galapagos Islands». Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 21 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1853.tb07165.x. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ Williams, Ernest E.; Anthony, Harold Elmer; Goodwin, George Gilbert (1952). «A new fossil tortoise from Mona Island West Indies and a tentative arrangement of the tortoises of the world». Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 99 (9): 541–560. hdl:2246/418.

- ^ Pritchard, Peter Charles Howard (1967). Living Turtles of the World. New Jersey: TFH Publications. p. 156.

- ^ Bour, R. (1980). «Essai sur la taxinomie des Testudinidae actuels (Reptilia, Chelonii)». Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (in French). 4 (2): 546.

- ^ Günther 1877, p. 85

- ^ a b DeSola, Ralph (1930). «The liebespiel of Testudo vandenburghi, a new name for the mid-Albemarle Island Galápagos tortoise». Copeia. 1930 (3): 79–80. doi:10.2307/1437060. JSTOR 1437060.

- ^ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). «Checklist of Chelonians of the World» (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 271–276. ISSN 1864-5755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Caccone, A.; Gentile, G.; Gibbs, J. P.; Fritts, T. H.; Snell, H. L.; Betts, J.; Powell, J. R. (October 2002). «Phylogeography and History of Giant Galapagos Tortoises». Evolution. 56 (10): 2052–2066. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00131.x. JSTOR 3094648. PMID 12449492. S2CID 9149151.

- ^ White, William M.; McBirney, Alexander R.; Duncan, Robert A. (1993). «Petrology and geochemistry of the Galápagos Islands: portrait of a pathological mantle plume». Journal of Geophysical Research. 98 (B11): 19533–19564. Bibcode:1993JGR….9819533W. doi:10.1029/93JB02018.

- ^ Kehlmaier, C.; Barlow, A.; Hastings, A. K.; Vamberger, M.; Paijmans, J. L.; Steadman, D. W.; Fritz, U. (2017). «Tropical ancient DNA reveals relationships of the extinct Bahamian giant tortoise Chelonoidis alburyorum». Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 284 (1846). doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.2235. PMC 5247498. PMID 28077774.

- ^ Pereira, A.G.; Sterli, J.; Moreira, F. R. R.; Schrago, C. G. (2017). «Multilocus phylogeny and statistical biogeography clarify the evolutionary history of major lineages of turtles». Molecular Phylogenetics. 113: 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.05.008. PMID 28501611.

- ^ Nicholls 2006, p. 68

- ^ Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Gibbs, James P.; Havill, Nathan; Fritts, Thomas H.; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2004). «Giant tortoises are not so slow: rapid diversification and biogeographic consensus in the Galápagos». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (17): 6514–6519. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.6514B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400393101. PMC 404076. PMID 15084743.

- ^ a b c Ciofi, Claudio; Wilson, Gregory A.; Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Marquez, Cruz; Gibbs, James P.; Tapia, Washington; Snell, Howard L.; Caccone, Adalgisa; Powell, Jeffrey R. (2006). «Phylogeographic history and gene flow among giant Galápagos tortoises on southern Isabela Island». Genetics. 172 (3): 1727–1744. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.047860. PMC 1456292. PMID 16387883.

- ^ a b c Pritchard 1996, p. 65

- ^ a b Russello, Michael A.; Poulakakis, Nikos; Gibbs, James P.; Tapia, Washington; Benavides, Edgar; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2010). «DNA from the past informs ex situ conservation for the future: an extinct species of Galapagos tortoise identified in captivity». PLOS ONE. 5 (1): e8683. Bibcode:2010PLoSO…5.8683R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008683. PMC 2800188. PMID 20084268.

- ^ Garrick, Ryan; Benavides, Edgar; Russello, Michael A.; Gibbs, James P.; Poulakakis, Nikos; Dion, Kirstin B.; Hyseni, Chaz; Kajdacsi, Brittney; Márquez, Lady; Bahan, Sarah; Ciofi, Claudio; Tapia, Washington; Caccone, Adalgisa (2012). «Genetic rediscovery of an ‘extinct’ Galápagos giant tortoise species». Current Biology. 22 (1): R10–1. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.004. PMID 22240469.

- ^ Pak, Hasong; Zaneveld, J.R.V. (1973). «The Cromwell Current on the east side of the Galapagos Islands» (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 78 (33): 7845–7859. Bibcode:1973JGR….78.7845P. doi:10.1029/JC078i033p07845. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2016.

- ^ Nicholls 2006, p. 161

- ^ a b Russello, Michael A.; Beheregaray, Luciano B.; Gibbs, James P.; Fritts, Thomas; Havill, Nathan; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2007). «Lonesome George is not alone among Galapagos tortoises» (PDF). Current Biology. 17 (9): R317–R318. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.002. PMID 17470342. S2CID 3055405.

- ^ Russello, Michael A.; Glaberman, Scott; Gibbs, James P.; Marquez, Cruz; Powell, Jeffrey R.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2005). «A cryptic taxon of Galapagos tortoise in conservation peril». Biological Letters. 1 (3): 287–290. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0317. PMC 1617146. PMID 17148189.

- ^ a b Chiari, Ylenia; Hyseni, Chaz; Fritts, Tom H.; Glaberman, Scott; Marquez, Cruz; Gibbs, James P.; Claude, Julien; Caccone, Adalgisa (2009). «Morphometrics Parallel Genetics in a Newly Discovered and Endangered Taxon of Galápagos Tortoise». PLOS ONE. 4 (7): e6272. Bibcode:2009PLoSO…4.6272C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006272. PMC 2707613. PMID 19609441.

- ^ Ciofi, Claudio; Milinkovitch, Michel C.; Gibbs, James P.; Caccone, Adalgisa; Powell, Jeffrey R. (2002). «Microsatellite analysis of genetic divergence among populations of giant Galápagos tortoises». Molecular Ecology. 11 (11): 2265–2283. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01617.x. PMID 12406238. S2CID 30172900.

- ^ a b c d e Poulakakis, N.; Edwards, D. L.; Chiari, Y.; Garrick, R. C.; Russello, M. A.; Benavides, E.; Watkins-Colwell, G. J.; Glaberman, S.; Tapia, W.; Gibbs, J. P.; Cayot, L. J.; Caccone, A. (21 October 2015). «Description of a New Galapagos Giant Tortoise Species (Chelonoidis; Testudines: Testudinidae) from Cerro Fatal on Santa Cruz Island». PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138779. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038779P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138779. PMC 4619298. PMID 26488886.

- ^ Marris, E. (21 October 2015). «Genetics probe identifies new Galapagos tortoise species». Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18611. S2CID 182351587.

- ^ a b «Yale team identifies new giant tortoise species in Galapagos». Yale News. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ «Pinzón Island, Galápagos». Island Conservation. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ «Giant Tortoise Webcam Project». Galapagos Conservancy. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan (28 October 2014). «Giant tortoise makes ‘miraculous’ stable recovery». BBC News. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Picheta, Rob (11 January 2020). «This tortoise had so much sex he saved his species. Now he’s going home». CNN. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ «Galapagos: ‘extinct’ giant tortoise found». Deutsche Presse Agentur. 20 February 2019 – via news.com.au.

- ^ a b «Santa Fé». Galapagos Conservancy, Inc. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Tapia A., Washington; Goldspiel, Harrison; Sevilla, Christian; Málaga, Jeffreys; Gibbs, James P. (1 January 2021), Gibbs, James P.; Cayot, Linda J.; Aguilera, Washington Tapia (eds.), «Chapter 24 — Santa Fe Island: Return of tortoises via a replacement species», Galapagos Giant Tortoises, Biodiversity of World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes, Academic Press, pp. 483–499, ISBN 978-0-12-817554-5, retrieved 29 March 2021

- ^ a b c d MacFarland, C.G. (1972). «Giant tortoises, goliaths of the Galapagos». National Geographic Magazine. 142: 632–649.

- ^ de Berlanga, Tomás (1535). Letter to His Majesty … describing his voyage from Panamá to Puerto Viejo. Coleccion de Documentos Ineditos relativos al Descubrimiento, Conquista y Organizacion de las Antiguas Posesiones Españolas de América y Oceania (in Spanish). Vol. 41. Madrid: Manuel G. Hernandez. pp. 538–544.

- ^ a b c d e f Darwin 1839, pp. 462–466

- ^ Ebersbach, V.K. (2001). Zur Biologie und Haltung der Aldabra-Riesenschildkröte (Geochelone gigantea) und der Galapagos-Riesenschildkröte (Geochelone elephantopus) in menschlicher Obhut unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Fortpflanzung (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in German). Hannover: Tierärztliche Hochschule.

- ^ a b c Fritts, T.H. (1983). «Morphometrics of Galapagos tortoises: evolutionary implications». In Bowman, I.R.; Berson, M.; Leviton, A.E (eds.). Patterns of evolution in Galapagos organisms. San Francisco: American Association for the Advancement of Science. pp. 107–122. ISBN 978-0-934394-05-5.

- ^ McAllister, C. T.; Duszynski, D. W.; Roberts, D. T. (2014). «A New Coccidian (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from Galápagos Tortoise, Chelonoidis sp. (Testudines: Testudinidae), from the Dallas Zoo». Journal of Parasitology. 100 (1): 128–132. doi:10.1645/13-307.1. PMID 24006862. S2CID 25989466.

- ^ Caporaso, F. The Galápagos Tortoise Conservation Program: the Plight and Future for the Pinzón Island Tortoise.

- ^ Pritchard 1996, p. 18

- ^ Auffenberg, Walter (1971). «A new fossil tortoise, with remarks on the origin of South American testudinines». Copeia. 1971 (1): 106–117. doi:10.2307/1441604. JSTOR 1441604.

- ^ Dawson, E.Y. (1966). «Cacti in the Galápagos islands, with special reference to their relations with tortoises». In Bowman, R.I (ed.). The Galápagos. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 209–214.

- ^ de Neira, Lynn E. Fowler; Roe, John H. (1984). «Emergence success of tortoise nests and the effect of feral burros on nest success on Volcán Alcedo, Galapagos». Copeia. 1984 (3): 702–707. doi:10.2307/1445152. JSTOR 1445152.

- ^ a b c Schafer, Susan F.; Krekorian, C. O’Neill (1983). «Agonistic behavior of the Galapagos tortoise, Geochelone elephantopus, with emphasis on its relationship to saddle-backed shell shape». Herpetologica. 39 (4): 448–456. JSTOR 3892541.

- ^ Marlow, Ronald William; Patton, James L. (1981). «Biochemical relationships of the Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus)». Journal of Zoology. 195 (3): 413–422. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1981.tb03474.x.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Charles C. (1966). «Notes on the behavior and ecology of the Galapagos tortoise on Santa Cruz island». Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science. 46: 28–32.

- ^ Jackson, M.H. (1993). Galápagos, a natural history. University of Calgary Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-895176-07-0.

- ^ Daggett, Frank S. (1 January 1915). «A Galapagos Tortoise». Science. 42 (1096): 933–934. Bibcode:1915Sci….42..933D. doi:10.1126/science.42.1096.933-a. JSTOR 1640003. PMID 17800728. S2CID 5198874.

- ^ Cayot, Linda Jean (1987). Ecology of giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) in the Galápagos Islands (PhD thesis). Syracuse University.

- ^ Hatt, Jean-Michel; Class, Marcus; Gisler, Ricarda; Liesegang, Annette; Wanner, Marcel (2005). «Fiber digestibility in juvenile Galapagos tortoises (Geochelone nigra) and implications for the development of captive animals». Zoo Biology. 24 (2): 185–191. doi:10.1002/zoo.20039.